Family formations in fertility treatment 2022

Preliminary UK family type statistics for IVF and DI treatment, storage, and donation

Published: November 2024

Download the underlying dataset as .xlsx

Table of contents

- Main points

- Introduction

- Section 1: The proportion of female same-sex couples and single patients having fertility treatment has changed

- Section 2: IVF birth rates highest among female same-sex couples

- Section 3: Single patients are starting IVF younger than previous years

- Section 4: Patient population changes between those storing eggs and thawing them

- Section 5: Average IVF multiple birth rate decreased across all family types

- Section 6: Female same-sex couples and single patients had the lowest levels of NHS funding

- Section 7: Up to two-thirds of surrogacy cycles were same-sex couples with a small number of single intended parents

- Conclusion and next steps

- About our data

Main points

- Most in vitro fertilisation (IVF) treatments in 2022 were among opposite-sex couples (89%). However, the proportion of treatments among female same-sex couples and single patients more than doubled from 2012 to 2022, from 2% to 4% and 2% to 6%, respectively.

- Female same-sex couples are now having IVF more than donor insemination (DI), with IVF accounting for 39% of their treatment cycles in 2012 and rising to 58% in 2022.

- Reciprocal IVF, where one partner has an embryo created with an egg from the other partner transferred to their uterus, is estimated to have accounted for 1 in 6 IVF cycles among female same-sex couples in 2022.

- Female same-sex couples and single patients had the highest birth rates per embryo transferred at 43% and 40% respectively, compared to 35% among opposite-sex couples for patients aged 18-34 in 2018-2022.

- Single patients started IVF later than other family types at just over 36 in 2022, compared to 34 for female same-sex couples and 35 for opposite-sex couples. This compared to Office for National Statistics (ONS) figures, that include all live births, where the overall average age that women in England and Wales had their first birth in 2022 was 29.21.

- Those storing eggs were mostly single patients, making up 89% of all egg storage cycles, whereas opposite-sex couples most commonly thawed eggs for treatment accounting for 85% of egg thawing cycles in 2018-2022.

- Average multiple birth rates decreased across all family types, decreasing overall from 12-13% in 2013-17 to 5-6% in 2018-2022, with little difference between family types.

- IVF funding was least common for single patients and female same-sex couples, aged 18-39, at 18% and 16% NHS-funded respectively, compared to 52% among opposite-sex couples in 2022.

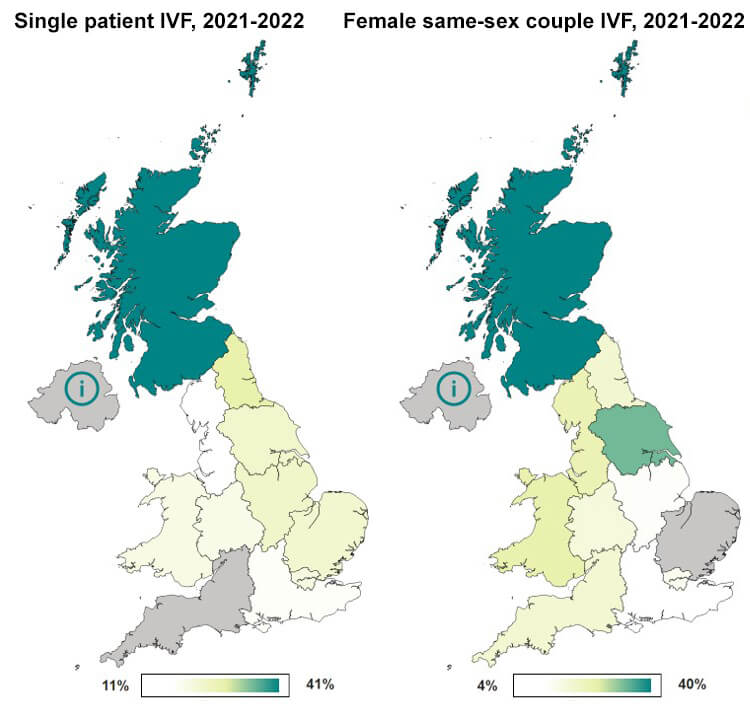

- Scotland had the highest level of first NHS-funded IVF for patients aged 18-39, across all family types, with 82% of opposite-sex couples funded, compared to 40% and 41% funded among female same-sex couples and single patients respectively in 2021-22.

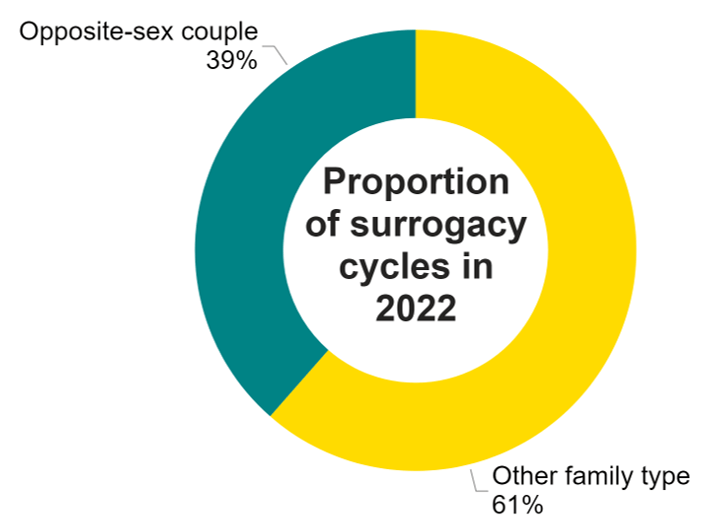

- In 2022, opposite-sex couples made up at least 39% of surrogacy cycles, with other family types making up the other 61%. This is the first year this data has been available.

Introduction

This report highlights differences in use and outcomes of fertility treatment in the UK by family type from 2012-22 and follows our first publication on family formations in fertility treatment in 2020.

While most fertility treatments in the UK are among opposite-sex couples, the number of female same-sex couples and single patients undergoing fertility treatments is increasing year on year. The treatment these patient groups receive is also changing, with a notable shift from DI use to IVF. There are, however, disparities in access to treatment between different family types due to lower levels of NHS funding. In the concluding section, we set out several actions for ourselves as the regulator and for others, to reduce disparities – both in access to and experiences of fertility treatment – for different family types.

Family type comparisons are limited by the data we hold on our national register. Classification of family types are based on sex assigned at birth and linked partner details; information on sexual orientation and gender identity are not available on the register. Birth rates by family type and additional patient information, such as ethnicity, are available on the HFEA dashboard.

Where possible, we have included broad interpretations of why differences may exist by family type and have referenced academic or other publications that provide further information.

1. The proportion of female same-sex couples and single patients having fertility treatment has changed

IVF and DI treatments in the UK have increased in recent years with the number of IVF cycles increasing from around 60,200 in 2012 to 75,500 in 2022 (+25%), while DI has increased from 4,500 to 5,600 (+26%). Most treatments were among opposite-sex couples, though use has increased most among single patients and female same-sex couples, who now account for around 1 in 6 of all IVF and DI treatments. Patients having IVF or DI treatment increased from around 45,300 to 47,000 for opposite-sex couples, with female same-sex couples and single patients more than doubling from 1,300 to 3,300 and 1,400 to 4,800, respectively.

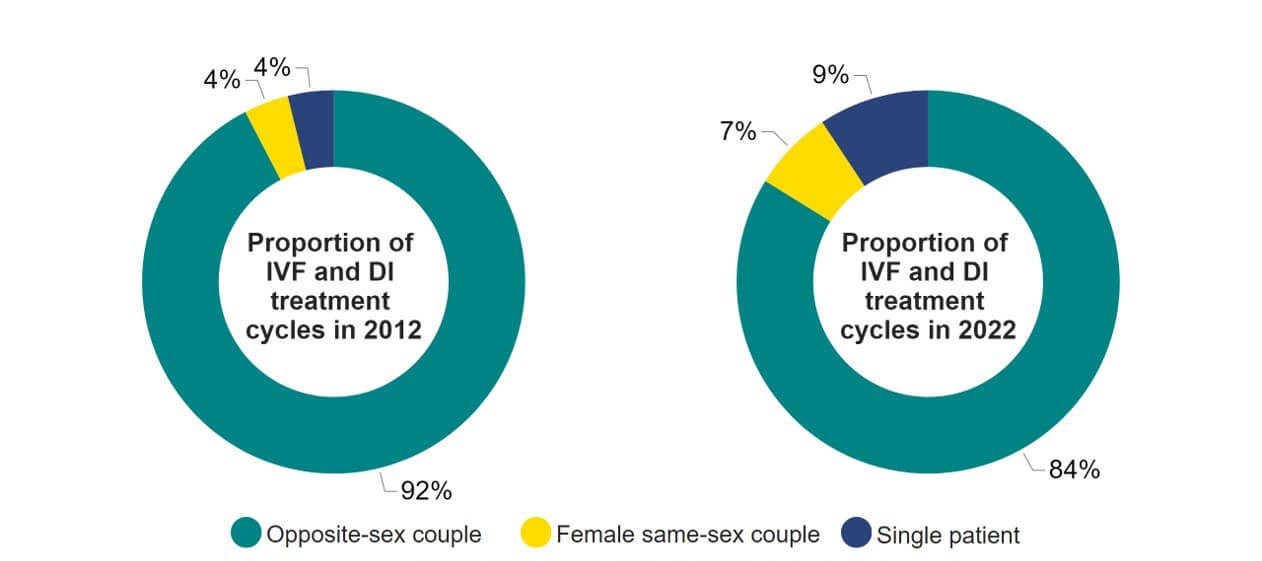

Patients in opposite-sex couples accounted for 96% of IVF cycles in 2012, with female same-sex couples and single patients accounting for 2% each (Figure 1). The proportion of opposite-sex couples having IVF decreased to 89% in 2022, with female same-sex couples increasing to 4% and single patients increasing to 6%.

Most DI treatments in 2012 were among opposite-sex couples, accounting for 38% of DI treatments, with female same-sex couples (33%) and single patients (29%) making up the remaining treatments. This contrasts with 2022, where single patients most commonly used DI treatments, accounting for 47% of DI treatments, followed by female same-sex (41%) and opposite-sex couples (11%). See our Trends in egg, sperm and embryo donation 2020 report for more information on donation.

Although fertility treatment is becoming more common among single patients and female same-sex couples, areas for improvement remain. Several patients raised frustrations in our National Patient Survey 2021 around inclusivity, including incorrect terminology used by staff or in relevant paperwork. Additionally, many patients noted the importance to them in choosing an LGBTQIA+ friendly clinic for their fertility treatment.

Figure 1. The proportion of female same-sex couples and single patients having fertility treatment has changed

Proportion of IVF and DI cycles by family type, 2012 and 2022 (preliminary 2022 data)

Note figure 1: Data is preliminary for 2022. Includes patients undergoing treatment where the cycle was begun with the intention of immediate treatment, instead of storing eggs or embryos for future use.

Download the underlying data for Figure 1 as Excel Worksheet

Overall, the proportion of IVF and DI treatments across the UK remained similar over the decade, with IVF accounting for 93% of all treatments in both 2012 and 20222. However, these averages hide notable changes in treatment use among single patients and female same-sex couples over this period.

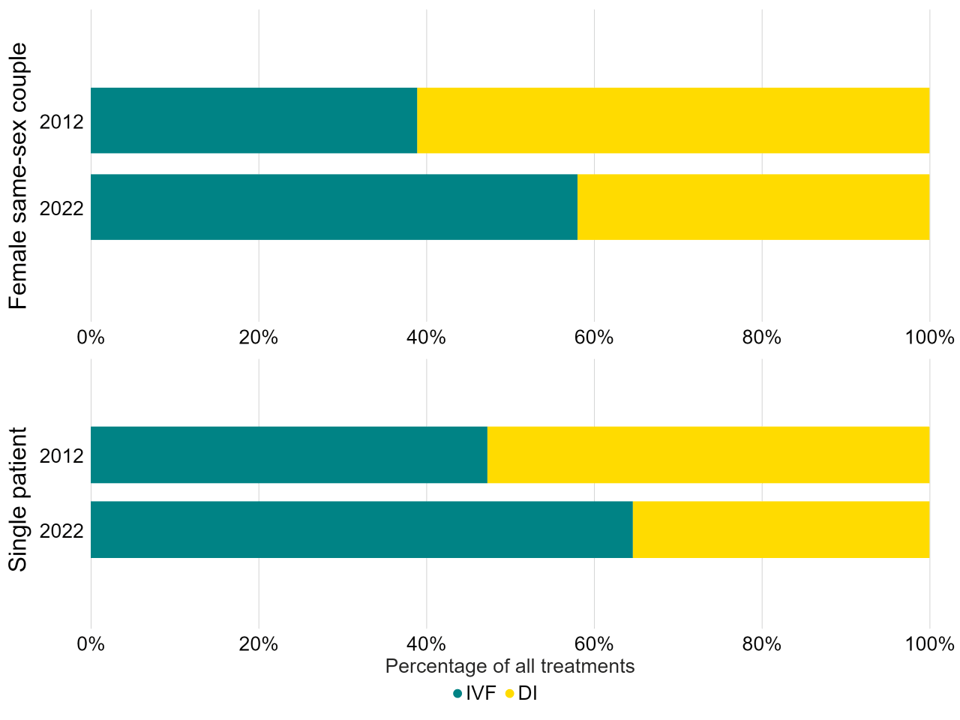

IVF treatment has increased among both single patients and female same-sex couples (Figure 2). IVF accounted for 39% of female same-sex couple treatment cycles in 2012, rising to a record high of 58% in 2022, with 2021 being the first year IVF was the most common treatment among this group. Similarly, IVF accounted for 65% of all treatments among single patients in 2022, an increase from 47% in 2012. Opposite-sex couples remained similar from 2012 to 2022, with IVF accounting for around 98% across all yearsI.

Increased IVF cycles among female same-sex couples will in part relate to a rise in the use of reciprocal IVFII. We estimate that around 1 in 6 female same-sex couple IVF cycles were reciprocal IVF in 2022, with 384 patients having reciprocal IVF in 20223.

While IVF is one of the most invasive and expensive treatments per cycle, more single patients and female same-sex couples are choosing it over DI for several reasons such as higher birth rates per cycle, shorter time to pregnancy, lower multiple birth rates, lower overall donor sperm cost due to fewer cycles, and the possibility of storing embryos for future treatments.

Figure 2. Female same-sex couples and single patients increasingly having IVF

Proportion of IVF and DI cycles by family type, 2012 and 2022 (preliminary 2022 data)

Note figure 2: Data is preliminary for 2022. Includes patients undergoing treatment where the cycle was begun with the intention of immediate treatment, instead of storing eggs or embryos for future use.

Download the underlying data for Figure 2 as Excel Worksheet

2. IVF birth rates highest among female same-sex couples

The average overall birth rate from IVF using fresh embryo transfers and patients’ eggs increased from 18% per embryo transferred in 2012 to 25% in 2022.

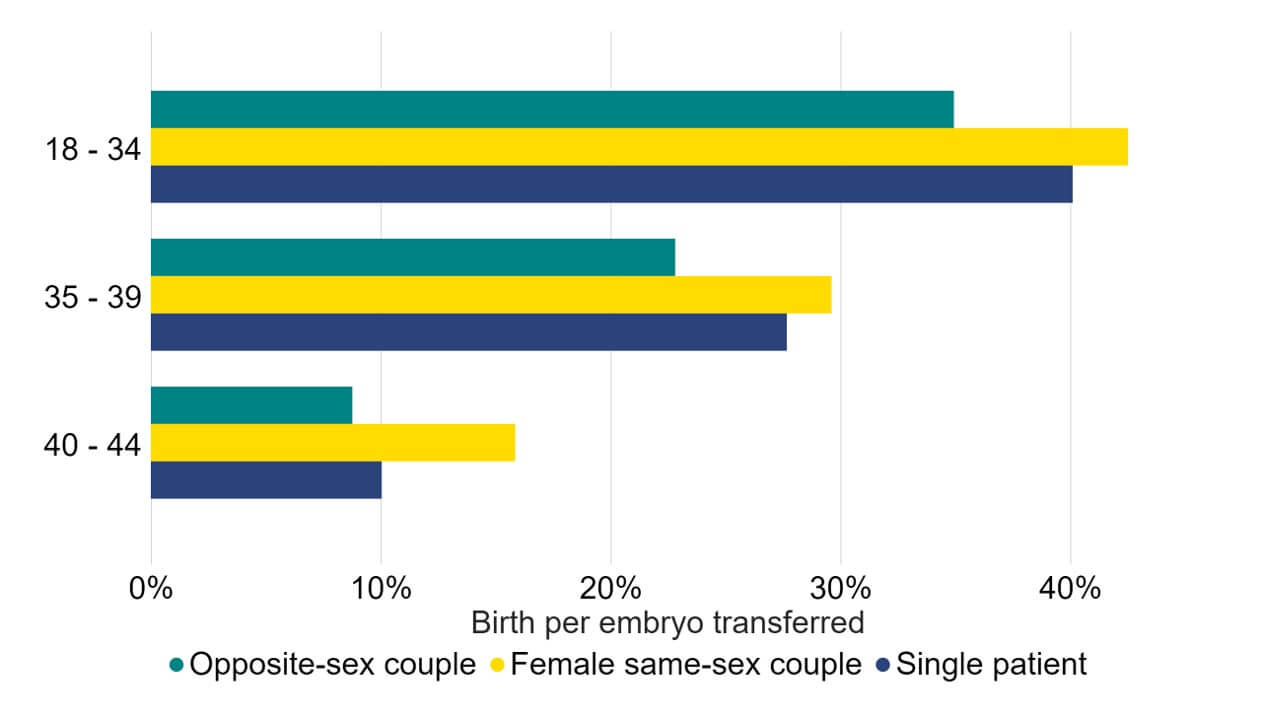

Birth rates among opposite-sex couples were the lowest across all ages, with a 35% birth rate per embryo transferred among patients aged 18-34 and 9% aged 40-44 (Figure 3). Female same-sex couples had the highest birth rates at 43% for patients aged 18-34, decreasing to 16% for patients aged 40-44. Single patients had slightly lower birth rates, at 40% for patients aged 18-34 and 10% for patients aged 40-44.

The higher birth rates among single patients and female same-sex couples may relate to the reasons for having IVF. Opposite-sex couples undergoing IVF are likely to suffer from infertility whereas single patients and female same-sex couples are primarily having IVF for other reasons such as use of donor sperm or reciprocal IVF (although some of them may also have underlying infertility or subfertility).

Some difference in birth rates may be due to use of sperm donors by female same-sex couples and single patients. Donor sperm is typically from younger men (median age of 33)4 and must meet certain quality criteria, whereas male partners are older (median age of 37) and may have infertility issues.

Figure 3. IVF birth rates highest among female same-sex couples

Fresh embryo transfer IVF birth rate per embryo transferred using patient eggs by family type, 2018-2022 (preliminary 2019-2022 data)

Note figure 3: Birth rates per embryo transferred for 2019-2022 are preliminary and have not been validated. This data includes IVF treatment cycles using their own eggs and fresh embryo transfers, and begun with the intention of immediate treatment, instead of storing eggs or embryos for future use. Treatments using PGT-A/M/SR, donor eggs or surrogacy, and treatments in which a pregnancy was recorded and no birth outcome recorded have been excluded.

Download the underlying data for Figure 3 as Excel Worksheet

3. Single patients are starting IVF younger than previous years

In 2022, the average age of patients starting IVF treatment was over 35 years old for the first time, rising from age 34.3 in 2012 to 35.1 in 20222. Average age when starting IVF varied by family type, with single patients making up the oldest group.

Average age of first IVF treatment for opposite-sex couples increased from age 34.3 to 35.0 from 2012 to 2022 (Figure 4). In contrast, the average age for single patients decreased from age 37.9 to 36.4, the lowest average age for single patients since data collection began in 2008. The average age at first IVF treatment for female same-sex couples and surrogatesIII remained similar from 2012-2022 around 34.0 years of age.

The decrease in age at first IVF treatment for single patients may have been influenced by factors such as a reduction in social stigma and the COVID-19 pandemic (where decision-making may have been impacted)5, contributing to the 1.5 year drop over the decade.

Figure 4. Single patients are starting IVF earlier than previous years

Average age at first IVF cycle among patients aged 18-49 by family type, 2012-2022 (preliminary 2020-2022 data)

Note figure 4: Data is preliminary for 2020-2022. This data includes the average (mean) age of patient’s first IVF cycle begun with the intention of immediate treatment, instead of storing eggs or embryos for future use.

Download the underlying data for Figure 4 as Excel Worksheet

4. Patient population changes between those storing eggs and thawing them

We have seen an increase in storing eggs for future use in fertility treatments. Egg storage cycles account for 5% of all cycles carried out at UK clinics in 2022 and is one of the fastest growing treatments, having increased from around 2,600 cycles in 2019 to 4,600 in 20222.

From 2018-2022, those storing eggs were mostly single patients, making up 89% of all egg storage cycles (Figure 5). Opposite-sex couples accounted for 10% of egg storage cycles, while female same-sex couples accounted for 1%. In contrast, the majority of those who thawed eggs for treatment were opposite-sex couples, accounting for 85% of egg thaw cycles. Single patients accounted for 13% of egg thawing cycles, while female same-sex couples accounted for 2%IV.

Egg storage data collected by the HFEA does not distinguish between reasons for storing eggs, such as elective fertility preservation or for medical reasons. However, using NHS funding as a proxy for medical egg storage indicates that at least 16% of egg storage cycles were for medical reasons in 2018-22. See underlying dataset for more details.

Figure 5. Patient population changes between those storing eggs and thawing them

Egg storage and thawing cycles by family type, 2018-2022 (preliminary 2020-2022 data)

Note figure 5: This data included is preliminary for 2020-2022. This data does not include cycles where eggs were collected for the purposes of donation. Egg storage data collected by the HFEA includes both elective fertility preservation as well as egg storage for medical reasons. Egg storage data includes only eggs intended for storage rather than use in immediate treatment or donation. Egg thaw cycles include treatments where an egg was thawed and used in IVF.

Download the underlying data for Figure 5 as Excel Worksheet

5. Average IVF multiple birth rate decreased across all family types

Multiple births cause increased risk of health problems for patients and their babies. In the early 1990s the average UK multiple birth rate from IVF was around 28%. Following the launch of the ‘One at a time’ campaign and the introduction of a multiple birth rate target, multiple births have successfully decreased across the UK to a record low of 4% in 20222.

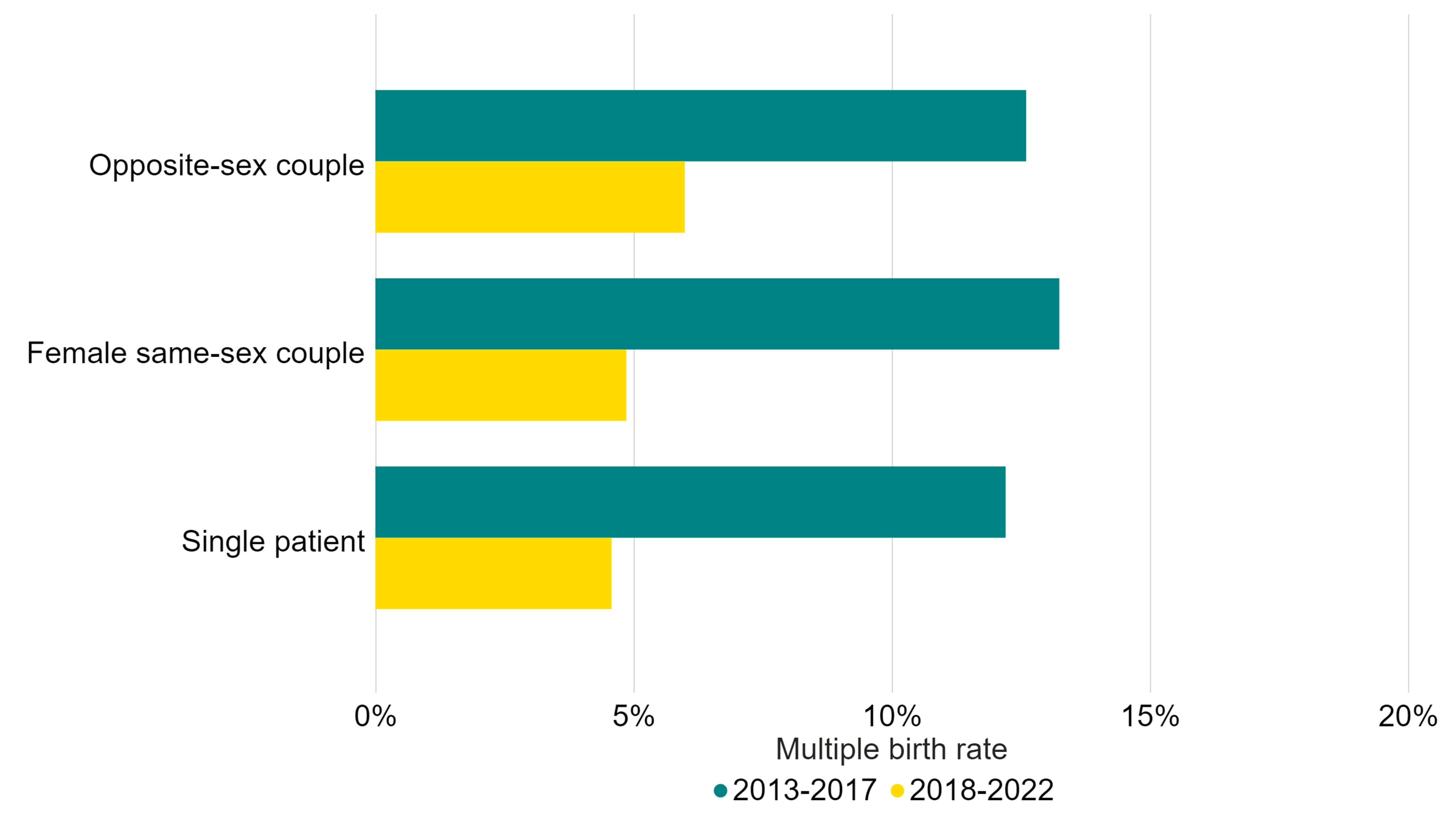

Multiple births decreased from 12-13% in 2013-17 to 5-6% in 2018-2022 across all family types. The multiple birth rate decreased from 13% to 6% among opposite-sex couples, 13% to 5% among female same-sex couples, and 12% to 5% among single patients (Figure 6). Surrogacy patients had the largest decrease in multiple births from 14% in 2013-2017 to 5% in 2018-22III.

For further information regarding multiple births, please see our Fertility treatment 2022: preliminary trends and figures report.

Figure 6. Average IVF multiple birth rate decreased across all family types

IVF average multiple birth rate among patients aged 18-49 by family type, 2013-17 and 2018-22 (preliminary 2019-2022 data)

Note figure 6: Data for 2019-2022 are preliminary. This data includes cycles using either patient or donor eggs and IVF treatment cycles begun with the intention of immediate treatment, instead of storing eggs or embryos for future use. Treatments in which a pregnancy was recorded and no birth outcome recorded have been excluded.

Download the underlying data for Figure 6 as Excel Worksheet

6. Female same-sex couples and single patients had the lowest levels of NHS funding

NHS-funded IVF cycles have decreased across the UK from 40% in 2012 to 27% in 20222. Data included in this section only includes treatments among patients aged 18-39 with no previous live births or IVF cycles, to reduce the impact of other variations by family type in comparisons drawn.

NHS-funded IVF cycles for patients aged 18-39 across the UK declined in recent years, from 65% in 2012 to 48% in 2022 (Figure 7). Similarly, NHS-funded DI cycles decreased from 22% to 16%. NHS-funded cycles varied by family type, with female same-sex couples and single patients least likely to be fundedV.

Opposite-sex couples aged 18-39, were three times as likely to have NHS-funded cycles, although there was a decrease in funded cycles from 67% in 2012 to 52% in 2022. In contrast, there were small increases in funding for female same-sex couples and single patients changing from 12% in 2012 to 16% in 2022, and 17% to 18%, respectively.

Funding for DI for both female same-sex couples and single patients increased from 2012 to 2022, with the proportion of NHS-funded DI cycles among female same-sex couples at 6% in 2012, rising to 13% in 2022. Similarly, the proportion of NHS-funded DI cycles among single patients increased from 9% in 2012 to 12% in 2022. Though DI was most commonly used by female same-sex couples and single patients (see Section 1), DI cycles among opposite-sex couples were most commonly funded by the NHS, at 51% in 2012 and 45% in 2022.

Figure 7. Female same-sex couples and single patients had the lowest levels of NHS funding

Percentage of IVF cycles funded by NHS among patients aged 18-39, first IVF cycle with no previous live birth, 2012-2022 (preliminary 2020-2022 data)

Note figure 7: Data is preliminary for 2020-2022. This data includes patient’s first IVF treatment cycles begun with the intention of immediate treatment, instead of storing eggs or embryos for future use. This figure focuses on patients on their first IVF cycle with no previous live births as funding criteria vary by number of previous cycles and children.

Download the underlying data for Figure 7 as Excel Worksheet

NHS funding varies considerably across the UK depending on national funding criteria and local funding across Integrated Care Boards (ICBs) in England. In 2022, Scotland had the highest rate of overall NHS-funded IVF cycles among patients aged 18-39, at 78% compared to 53% in Wales and 45% in EnglandVI in 2022. National and local funding vary further when comparing by family types.

Scotland had the highest level of NHS-funded first IVF, aged 18-39, across all family types, with 82% of opposite-sex couples IVF funded through the NHS, compared to 40% and 41% among female same-sex couples and single patients respectively in 2021-22 (Figure 8). Notably, the proportion of IVF cycles receiving NHS funding among female same-sex couples nearly doubled from 22% in 2012-13 to 40% in 2021-22. Treatment in Scotland accounted for around 5-6% of first IVF cycles among female same-sex couples or single patients across the UK.

While NHS-funded IVF among single patients and female same-sex couples increased in some parts of the country, areas with larger proportions of patients from these groups have meant there is little change on a national level. For example, London accounted for 21% of female same-sex IVF cycles in the UK in 2021-2022, where female same-sex NHS-funded IVF cycles decreased from 13% in 2012-13 to 7% in 2021-22.

NHS-funded DI treatment was also highest in Scotland across all family types, with funding increasing across all family types. Since 2017, in Scotland, 6-8 NHS-funded DI cycles are required before accessing funded IVF, whereas most funding criteria in the UK require 6-12 self-funded DI cycles before qualifying. This is likely why 49% of female same-sex first IVF cycles in Scotland had a previous DI cycle in 2021-2022, compared to a national average of 36%.

Variations in funding by ethnicity may have additional impact on patients, see our Ethnic diversity in fertility treatment report for more information. Furthermore, NHS funding criteria in some devolved nations and ICBs, such as limitations on smoking status, BMI, and age, will also impact access funding.

Figure 8. NHS funding for female same-sex couples vary across UK nations and English regions

Percentage of IVF or DI cycles funded by NHS among patients aged 18-39 with no previous IVF cycles and no previous live birth, United Kingdom, 2012-2022 (preliminary 2020-2022 data)

Note figure 8: Data is preliminary for 2020-2022. This data includes patient’s first IVF or DI treatment cycles begun with the intention of immediate treatment, instead of storing eggs or embryos for future use. This figure focuses on patients with no previous live births or IVF cycles as funding criteria typically varies by the number of previous cycles and children.

Download the underlying data for Figure 8 as Excel Worksheet

7. Up to two-thirds of surrogacy cycles were same-sex couples with a small number of single intended parents

Surrogacy cycles accounted for 0.4% of all IVF treatments in 2022, with the number of surrogacy patients increasing from around 130 in 2012 to 230 in 2022. The HFEA does not regulate most aspects of surrogacy, see our Surrogacy webpage for more information, and this data is not an accurate overall figure of surrogacy in the UK.

In 2022, opposite-sex couples made up at least 39% of surrogacy cycles, with “other family types” making up the other 61% (Figure 9). Based on previously published data, the majority of the “other family type” category will likely be male same-sex couples6, although it will also contain a small number of female same-sex couples and single intended parents.

Figure 9. Up to two-thirds of surrogacy cycles were same-sex couples with a small number of single intended parents

Proportion of surrogacy cycles by family type, 2022 (preliminary 2022 data)

Note figure 9: Data is preliminary for 2020-2022. Includes patients undergoing treatment where the cycle was begun with the intention of immediate treatment, instead of storing eggs or embryos for future use. Opposite-sex couples are couples where both an intended mother and an intended father were recorded on the register. Other family types include all other surrogacy cycles, which may include opposite-sex couples in cases where the intended mother and father were not both recorded. See the Quality and Methodology report for further details.

Download the underlying data for Figure 9 as Excel Worksheet

Conclusion and next steps

Opposite-sex couples continue to account for the majority of treatment cycles in the UK, although our data shows that female same-sex couples and single patients are a growing patient population. IVF is increasingly used by single patients and female same-sex couples, with higher birth rates than opposite-sex couples, and multiple birth rates at comparable low levels across all family types.

There has been public discussion in recent years of inequalities in access and treatment by family types in the UK3. Reproductive choices are being expanded with recent changes to the law meaning that enhanced screening is no longer necessary for couples having reciprocal IVF and that people who have HIV with an undetectable viral load can now donate to known recipients. We will monitor the impact of these changes through our data.

Single patients and female same-sex couples continue to have lower rates of NHS funding than opposite-sex couples. While we do not regulate funding it is important to consider how these inequalities can be addressed going forward.

We will use the data we collect and feedback from licensed clinics and patients, to understand any inequalities in access and variations in use of fertility treatments in the UK, and take action where needed.

In the short term, we propose the following:

Improvements in information provision from healthcare providers

Healthcare providers and fertility clinics are encouraged to review the information they provide to better capture and represent the diversity of families and patients accessing treatment.

Clinics are reminded of the availability of gender-neutral forms for use in treatment to ensure patients receive an inclusive experience independent of their gender.

NHS commissioning

We encourage all those who commission fertility services to review their funding eligibility criteria to consider whether these have an adverse impact on access to treatment among particular patients or families.

HFEA information and collection

We have recently received responses from fertility patients for the third edition of our National Patient Survey. The information collected will be published to highlight where variations exist by family types, including publishing information on sexual orientation and gender.

The HFEA will provide information on how clinics can simplify submission of data on transgender patients, allowing future research to include information on gender identity.

About our data

This report uses preliminary treatment and pregnancy data for 2020-2022 and preliminary birth outcome data for 2019-2022. This is because the HFEA has recently launched a new data submission system for licensed clinics and migrated our fertility treatment and outcomes data to a new database. This data migration has resulted in delays which has prevented the validation of the 2020-2022 treatment and pregnancy data and 2019-2022 birth outcome data. Because of this, these statistics cannot be classified as official statistics. Data validation involves data quality checks that verify treatment, pregnancy and birth outcome data. Data validation is expected to be complete in 2025VII.

This report covers the period from 1991-2022 where data is available. Data for 1991 covers a partial year, starting in August 1991. The information that we publish is a snapshot of data provided to us by licensed clinics. Data from one clinic is excluded due to data reporting issues. The figures supplied in this report are from our data warehouse containing Register data as of 17 October 2024. Results are published according to the year in which the cycle was started. For further information, please see our Quality and Methodology report.

We do not collect data on reciprocal IVF, instead numbers of reciprocal IVF treatments have been estimated using other information collected on our register. For further information on reciprocal IVF and surrogacy, please see our Quality and Methodology report.

Unless stated otherwise, the data in this report refers to treatment cycles i.e. only those cycles which were begun with the intention of immediate treatment, instead of storing eggs or embryos for future use. Averages used are provided as mean values unless stated otherwise.

About the HFEA

The HFEA is the UK’s independent regulator of fertility treatment and research using human embryos. Set up in 1990 by the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Act, the HFEA is responsible for licensing, monitoring, and inspecting fertility clinics and research centres – and taking enforcement action where necessary – to ensure everyone accessing fertility treatment receives high quality care.

The HFEA is an ‘arm’s length body’ of the Department of Health and Social Care, working independently from Government providing free, clear, and impartial information about fertility treatment, clinics and egg, sperm, and embryo donation.

The HFEA collects and verifies data on all treatments that take place in UK licensed clinics which can support scientific developments and research and service planning and delivery.

The HFEA is funded by licence fees, IVF treatment fees and a small grant from UK central government. For more information, visit hfea.gov.uk.

Contact us regarding this publication

Media: press.office@hfea.gov.uk

Statistical: intelligenceteam@hfea.gov.uk

Accessibility: comms@hfea.gov.uk

Footnotes

- Opposite-sex couples are more likely to use partner sperm IUI rather than DI, which is not recorded on the HFEA register. In cases of male factor infertility intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) may be used.

- Reciprocal IVF (also known as ‘shared motherhood’ or ‘shared parenthood’) is where eggs are collected from one partner in a same-sex female or other LGBTQIA+ couple and fertilised with donor sperm. The resulting embryo is then transferred into the other partner’s womb, who carries the pregnancy.

- Data available in underlying dataset.

- Please note that egg storage and egg thawing data are not all the same patients returning to use their eggs within this period, for example patients included in the egg thawing figures may have frozen eggs prior to 2018.

- For data regarding family types split by ethnicity, please see the HFEA dashboard. This was not explored further in this report due to low numbers.

- We are unable to report values for Northern Ireland for comparison due to technical issues in reporting from the largest clinic in Northern Ireland.

- Data validation involves quality checking data submitted from licensed clinics across the UK to verify that treatment, pregnancy and birth outcome data are correctly recorded on our data Register.

Notes on Family formations in fertility treatment

- Office for National Statistics. Births by parents’ characteristics dataset, 2022 edition, Table 4 (2023).

- Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority. Fertility treatment 2022: preliminary trends and figures (2024).

- Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority. HFEA welcomes changes to the law on screening in fertility treatment (2024).

- Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority. Trends in egg, sperm and embryo donation 2020 (2022).

- Gürtin, Z., Jasmin, E., Da Silva, P., Dennehy, C., Harper, J., Kanjani, S. Fertility treatment delays during COVID-19: Profiles, feelings and concerns of impacted patients. Reproductive Biomedicine & Society Online, Volume 14, Pages 251-264 (2022).

- Horsey, K., Gibson, G., Lamanna, G., Priddle, H., Linara-Demakakou, E., Nair, S., Arian-Schad, M., Thackare, H., Rimington, M., Macklon, N., Ahuja, K. First clinical report of 179 surrogacy cases in the UK: implications for policy and practice, Reproductive BioMedicine Online, Volume 45, Issue 4, Pages 831-838 (2022).

| Publication date: |

|---|