Trends in egg, sperm and embryo donation 2020

Statistics on donation and donor treatments in the UK fertility sector

Published: November 2022

Download the underlying dataset as .xlsx

Table of contents

- Main points

- Foreword

- Section 1. Use of donor eggs, sperm and embryos has increased

- Section 2. Donor registrations have increased, though access to donors of ethnic minority backgrounds varies

- Section 3. Treatments using donor eggs, sperm and embryos less commonly funded by NHS

- Section 4. Donor eggs can increase birth rates for older patients

- Section 5. From 2023, donor-conceived people will be able to access information on their donors

- Section 6. Characteristics of egg and sperm donors have changed over time

- About our data

- Additional information

Main points

- Donor conception led to more than 4,100 births in 2019, accounting for 1 in 170 of all births and for nearly 1 in 6 births using IVF in the UK.

- The number of children born from donor sperm more than tripled from under 900 in 2006, to over 2,800 in 2019. This increase was driven by single patients, and patients in female same-sex relationships.

- IVF treatments using donated sperm or eggs were less commonly funded through the NHS, with 13% funded compared to around 40% of IVF treatments without donation from 2016-2020.

- More than half of new sperm donors registered in the UK were from donor imports in 2020, with 27% donating in the USA and 21% donating in Denmark.

- Asian and Black donors were underrepresented compared to the UK population. Asian egg donors represented 5% of egg donors compared to 10% of an age-matched population, and Black sperm donors were 2% of sperm donors compared to 4% of the population.

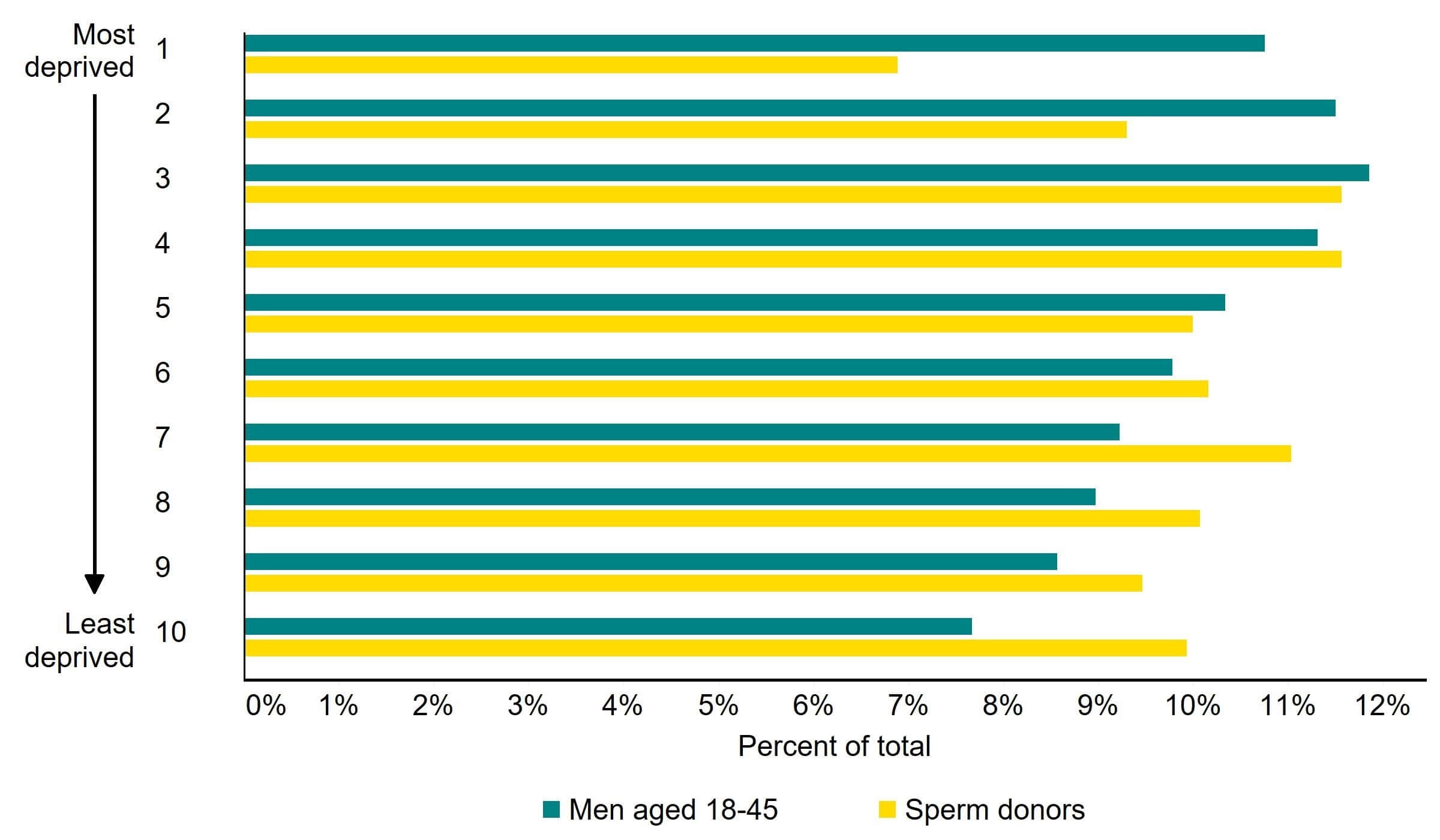

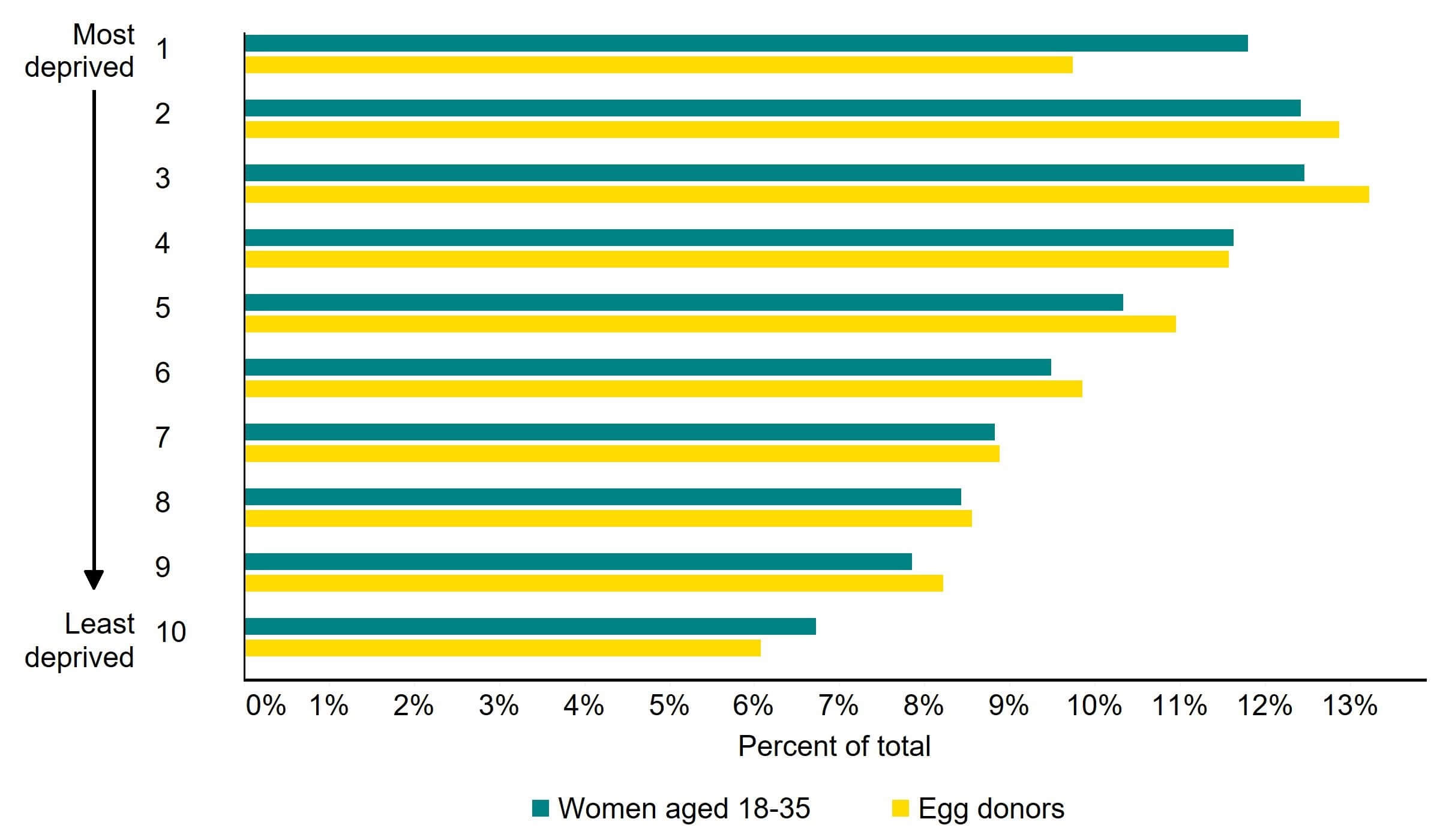

- Egg and sperm donors in England from 2011-2020 lived in similar or more affluent socio-economic areas than the general population. This, in combination with previous research, suggests that UK sperm and egg donors largely donate for altruistic reasons.

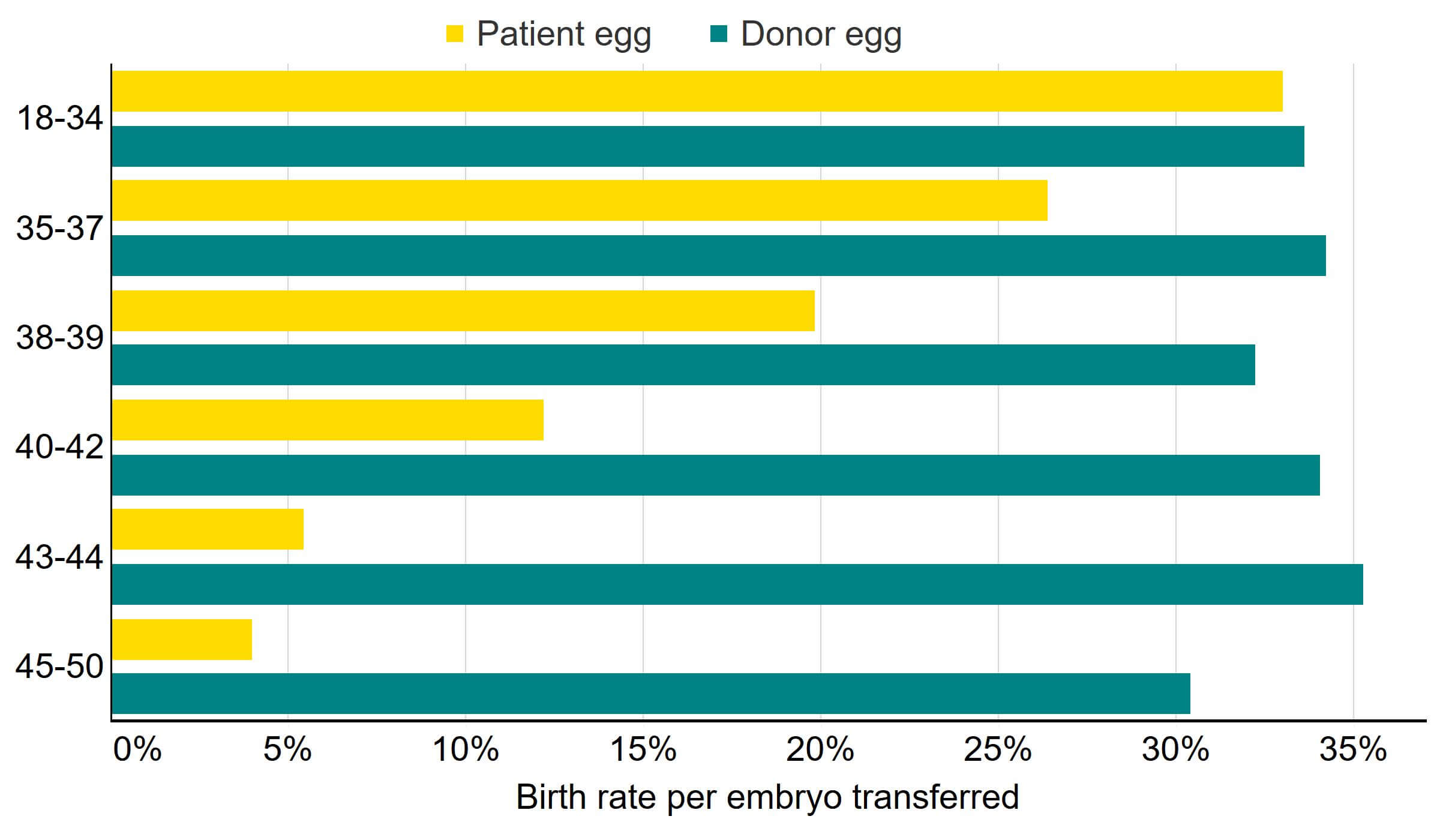

- IVF birth rates for patients aged 43-50 increased from 5% when using their own eggs to over 30% when using donor eggs from 2018-2019.

- From late 2023 onwards, donor-conceived people in the UK turning 18 will be able to apply to the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority (HFEA) to access identifying information about their donors.

Foreword

Some people will know that they need donor eggs or sperm from the start, for instance female same-sex couples and single patients will need donor sperm. However, using donor eggs or sperm may be a decision some people make because it may be their only or best possible chance of conceiving a child. This can be an emotionally difficult decision; it can mean that one or both parents may not be genetically linked to their child, and they may have worries about when and how to communicate to their child about their genetic origins.

It is no small act to donate sperm, eggs or embryos to help another person have a child. The vast majority of donors in the UK donate for altruistic reasons. It requires a time commitment to visit clinics, usually multiple appointments, and for egg donors a surgical procedure. It is illegal to pay donors more than reasonable expenses in the UK.

As a result of a change in UK law in 2005, it is not possible to donate sperm, eggs or embryos anonymously. This means that when a child conceived using egg, sperm or embryo donation reaches 18, they may choose to learn some of their donor’s identifiable information and try to contact them. This will enable almost all children conceived from donor sperm, eggs or embryos in the UK the right to request from the HFEA some personal identifiable information about their donor from late 2023 onwards. Currently, only a small number of children are eligible for this information due to donors re-registering to become identifiable.

The HFEA recommends that donors, and those using donor egg, sperm or embryos, receive specific and appropriate counselling where possible, which should be accessible through their clinic. The law requires all patients and donors to be offered counselling.

This report sets out how donation has changed in the UK over the last 30 years, when donation may be considered, and who has typically donated eggs or sperm. Feedback from patients in our National Patient Survey 2021 is also included throughout the report to give insights into what patients felt about egg and sperm donation. More information for those considering becoming a donor, or using donor egg, sperm or embryos in treatment, can be found on our website.

1. Use of donor eggs, sperm and embryos has increased

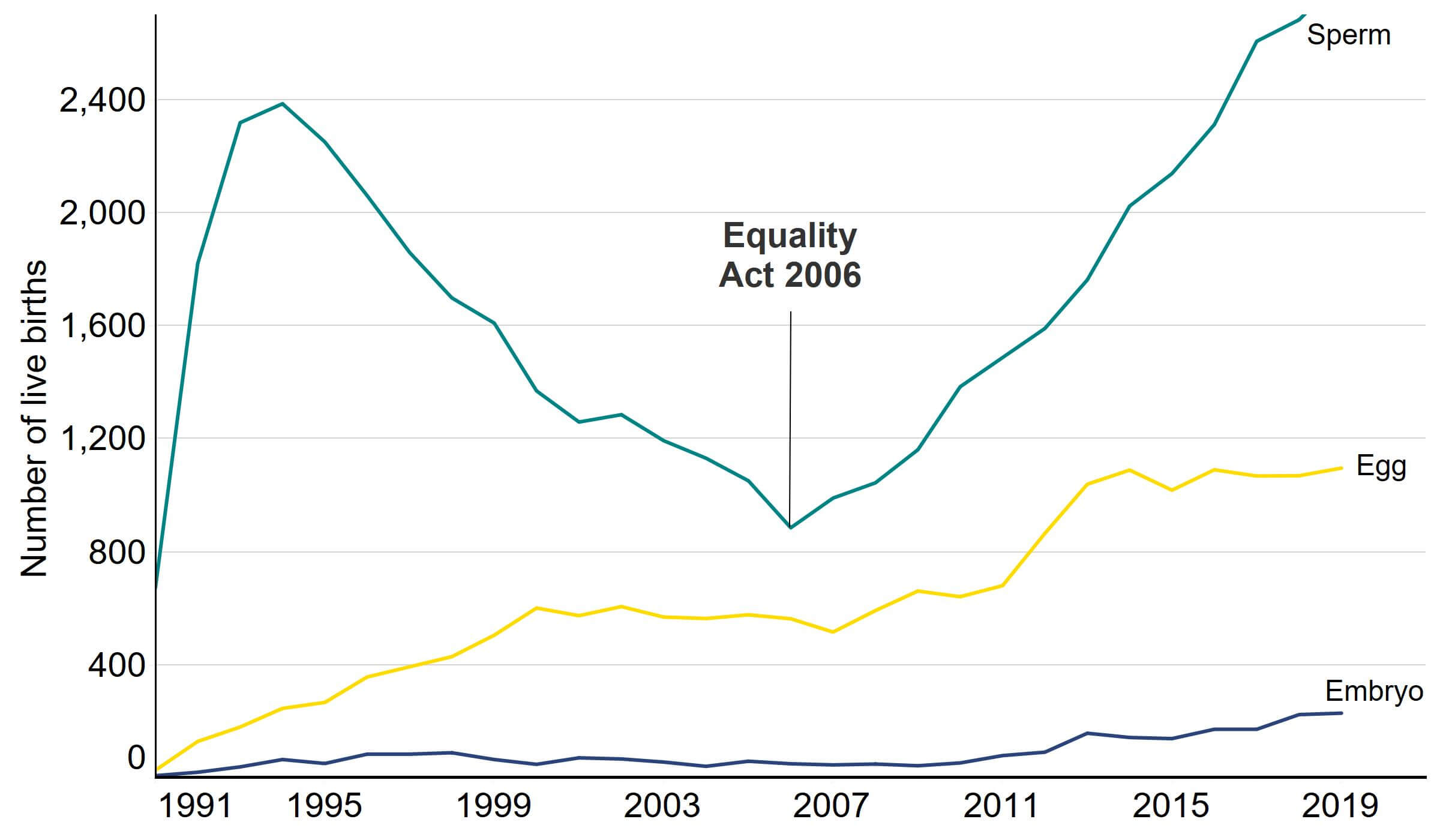

More than 70,000 donor-conceived children have been born since 1991. Births using donor eggs, sperm or embryos have increased from 1 in 450 of all UK births in 2006 to around 1 in 170 in 2019. Around 1 in 6 children born as a result of IVF treatment were conceived using donor eggs, sperm or embryos in 2019, a rise from 1 in 13 in 2007. Births using an egg, sperm or embryo donation increased by around 60% from about 2,500 in the mid 1990’s to around 4,100 in 2019 (Figure 1).

Almost 2,400 children were born in 1994 using donor sperm and this decreased to around 900 in 2006. This decline was due to the introduction of ICSI (Intracytoplasmic sperm injection), a procedure where sperm is injected into an egg, which enabled men with fertility problems to use their own sperm in treatment1-2.

Births from treatments using donor sperm more than tripled from under 900 in 2006 to more than 2,800 in 2019. This increase was mainly due to increased fertility treatment use by patients in female same-sex relationships and single patients following a change in the law which improved access for these patients and their partners3-4.

Births from treatments using donor embryos are least common, and have increased from under 50 births in 2010 to over 200 births in 2019. A minimum of 2% of children conceived in this way used an embryo donated by a couple, compared with up to 98% using separately donated eggs and sperm.

Figure 1. Births from donation almost tripled from 2006 to 2019

Number of live births from IVF or DI using donor sperm, eggs, or embryos, 1991-2019

Note figure 1: This data includes all live births resulting from the use of donor eggs, donor sperm, or donor embryos in IVF or DI. Years refer to the date of treatment, rather than the date of birth. The equivalent data for date of birth is available in the underlying dataset. Births from treatments using embryos includes treatments using both donated sperm and donated eggs, see Quality and methodology report for more information.

Download the underlying data for Figure 1 as Excel Worksheet

2. Donor registrations have increased, though access to donors of ethnic minority backgrounds varies

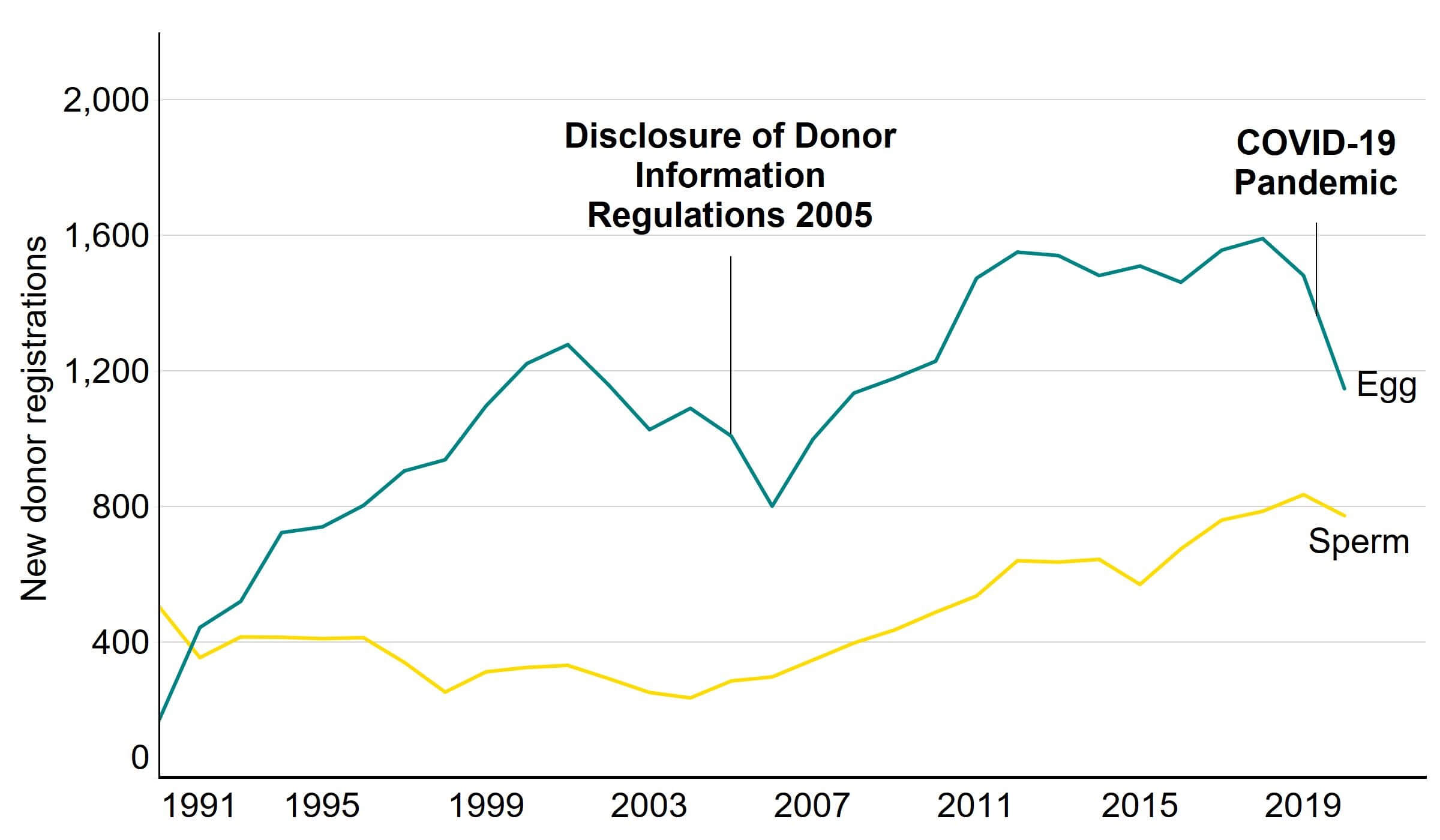

Total sperm and egg donor registrations have increased from less than 1,000 a year in the early 1990s to more than 2,300 in 2019 (Figure 2).

New egg donor registrations tripled from around 500 in the early 1990s to around 1,500 in the late 2010s. Egg donor registrations decreased temporarily in 2005-2006, likely due to a change in the law which gives donor-conceived people a right to access information about their donors once they reach the age of 185. See section 5 and rules around releasing donor information for more information.

Egg donor registrations decreased by 23% from 2019 to 2020, likely due to local lockdowns and hesitancy from potential donors over COVID-19 safety. See our Impact of COVID-19 on fertility treatment report for more information.

New sperm donor registrations doubled from around 400 registrations in the early 1990s to around 800 in the late 2010s. However, the proportion of imported sperm donations has increased in recent years (see Figure 3). There are typically fewer sperm donors per year than egg donors as sperm donors tend to provide multiple donations.

Figure 2. Sperm and egg donor registrations increased since 2006

Number of new egg and sperm donor registrations, 1991-2020

Note figure 2: This data uses new egg and sperm donor registrations only. Donors that registered multiple times will only be counted in the year of their first registration.

*These registrations include imports from persons who donated abroad. This represents a larger proportion of sperm donors in recent years, see Figure 3.

Download the underlying data for Figure 2 as Excel Worksheet

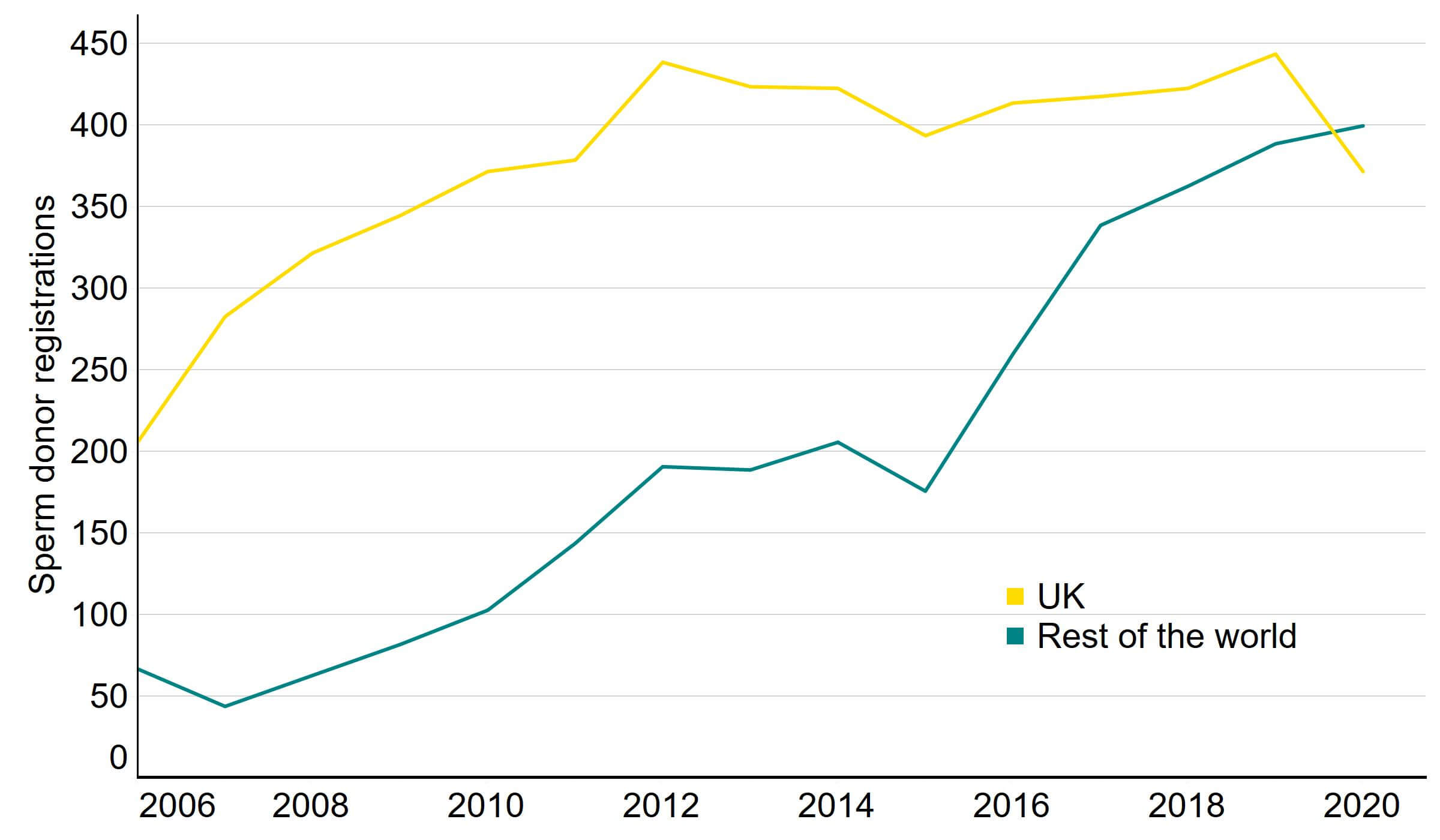

For the first time, over half (52%) of newly registered sperm donors in 2020 were from donor imports, an increase from around a quarter (22%) in 2010 (Figure 3). This has been caused by a rise in sperm imports, rather than a decline in UK donors. Newly registered sperm donors in the UK have remained consistent at around 400 donors per year since 2012, whereas newly registered sperm donors from imports have more than doubled from almost 200 in 2013 to 400 in 2020. Sperm donors outside of the 48% based in the UK were mainly based in the USA (27%) and Denmark (21%), with the remainder from other countries (4%).

Sperm from Mixed, Other and Black ethnicity donors were more likely to be imported than sperm from Asian and White donors, as was discussed in our Ethnic diversity in fertility treatment report. In contrast, almost all egg donors registered were in the UK. This is likely due to the difficulties in transporting eggs and UK guidelines requiring only reasonable expenses be paid to donors.

Around two-thirds of patients who had used donated eggs, sperm or embryos said they found it easy to access donor eggs, sperm or embryos in our National Patient Survey, though around a quarter of patients said they found them difficult to access. Several patients mentioned that they had imported sperm for treatment due to their difficulty finding a UK donor.

‘We were disappointed initially by [the] lack of choice for UK based sperm donors but were happy enough to choose from [a] Danish sperm bank. Feels a shame that sperm donation [isn’t] more popular in the UK.’

Figure 3. Over half of new sperm donors in 2020 were imports from people who donated abroad

New sperm donors registering in the UK and abroad, 2006-2020

Note figure 3: This data uses new sperm donor registrations only. Donors that registered multiple times will only be counted in the year of their first registration.

Download the underlying data for Figure 3 as Excel Worksheet

According to HFEA guidelines, when an egg and/or sperm donation is made in the UK, clinics should ensure they are only used to create up to a maximum of 10 families. In our survey, some patients expressed concern and confusion around how many times imported donor sperm could be used. As regulations differ in other countries, donations could be used to create additional families before or after the importation to the UK6.

‘The 10 family limit for donors is brilliant but it should be made clearer that this is not enforced worldwide’

UK guidelines require that imported donors meet the same identifiability requirements placed on UK donors (see section 5 for more on this). However, there may be practical difficulties around donor-conceived people wishing to contact their donor if their donor lives abroad.

In response to our survey, four in five patients who had used donor eggs, sperm or embryos (82%) said it was important that the donor’s ethnicity matched their own. However, some ethnic minority patients found it difficult to find donors matching their ethnicity.

‘We wanted a donor that matched our racial heritage as a couple. It took us 2 years to find a black donor that met UK guidelines but we still needed to import the donation from America.’

From 2016-2020, there were around 7,250 newly registered egg and 3,800 sperm donors in the UK. Most egg donors were White (88%), followed by Asian (4%), Mixed (4%), Black (3%) and Other (1%) ethnic groups (Table 1). About 87% of sperm donors were White and the remaining donors were made up of Asian (7%), Black (3%), Mixed (2%) and Other (2%) ethnic groups.

Disproportionately few donors were from Asian or Black backgrounds from 2016-2020. Asian patients also used eggs and sperm donation at lower rates than other ethnic groups. Around 7% of IVF cycles among Asian patients used egg and sperm donation in their treatment, compared to 8% for Other ethnicities and 13-15% for Black, Mixed and White patients. The lower proportion of Asian donors and lower use of donation among Asian ethnicities may be due to cultural and religious factors relating to donation7.

For more information on fertility treatment by ethnicity, see our Ethnic diversity in fertility treatment report.

| Table 1. Lower percentage of Asian and Black donors compared to population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| New UK donor registrations by ethnicity, 2016-2020 | |||

| % of egg donors | % of sperm donors | % of population aged 20-39 | |

| Asian | 4% | 7% | 10% |

| Black | 3% | 2% | 4% |

| Mixed | 4% | 3% | 2% |

| Other | 1% | 2% | 2% |

| White | 88% | 87% | 83% |

| Note table 1: This includes all UK-based donors registering for the first time from 2016-2020. UK population data is calculated using 2019 estimates for England and Wales, and 2011 census data for Northern Ireland and Scotland. | |||

Download the underlying data for Table 1 as Excel Worksheet

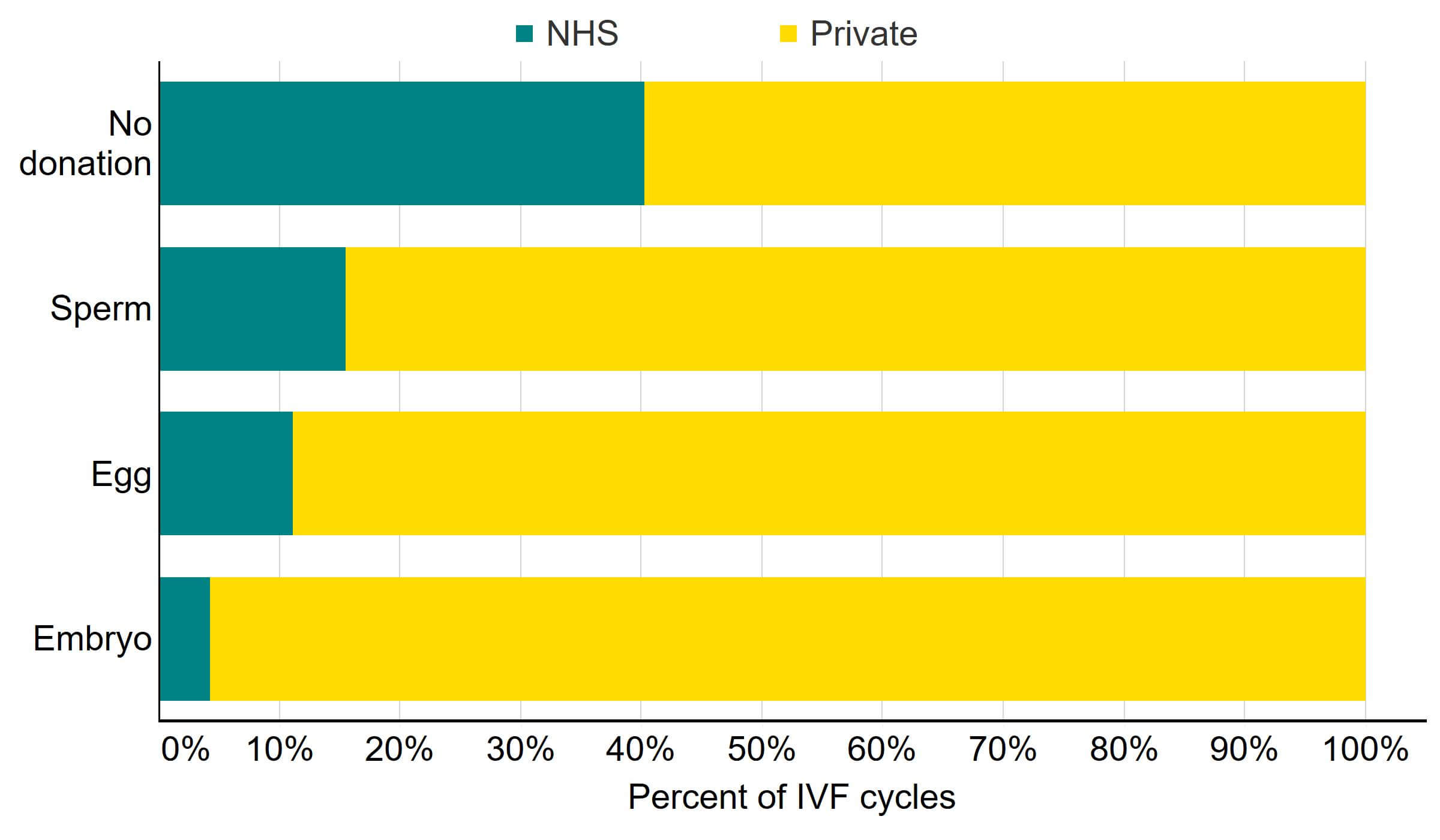

3. Treatments using donor eggs, sperm and embryos less commonly funded by NHS

Most IVF treatments in the UK are funded by patients themselves, with around 37% of IVF cycles funded through the NHS from 2016-2020. IVF treatments were less commonly funded by the NHS when using egg, sperm or embryo donation, with 13% NHS-funded compared to 40% for cycles using patient eggs and partner sperm from 2016-2020 (Figure 4). Around 15% of IVF treatments using donor sperm were funded by the NHS, followed by 11% of cycles using donor eggs, and 4% of cycles using donor embryos.

Fertility treatments among single patients and patients in female same-sex relationships all use donor sperm. Depending on national and local funding criteria8, single patients and patients in female-same-sex relationships may be required to have received multiple failed DI cycles before being eligible for IVF funding. From 2016-2020, around 8% of DI treatments among these patients were NHS-fundedI. See our Family formations in fertility treatment report for more information.

Patients aged 40-50 most commonly used donor eggs in IVF treatments (see section 4). Less than 4% of these patients received NHS funding from 2016-2020. Funding criteria set by devolved nations or locally throughout England may include maximum age restrictions though this varies by location.

When patients receive NHS funding for IVF using donor eggs or sperm this will cover their treatment, however the cost of donor sperm or eggs is often self-funded.

Figure 4. IVF treatments using donor eggs, sperm and embryos are less commonly funded by the NHS

Percentage of IVF cycles by funding and donation used, 2016-2020

Note figure 4: This data includes IVF treatments began with the intention of having a baby only.

Download the underlying data for Figure 4 as Excel Worksheet

In our National Patient Survey, several patients expressed difficulties accessing NHS funding for treatment using donor eggs, sperm and embryos. They described confusion around eligibility for funding and raised concerns that financial constraints could lead patients to use donors in unregulated settings.

‘The rules around eligibility for NHS funded treatment are unclear in relation to donor conception. We are ineligible for NHS treatment because we need to use a donor.’

‘It is extremely expensive! To the point where i[t] will exclude th[ose] that are single but cannot afford treatment (no NHS funding currently available) pushing them towards out of clinic treatments with unregulated donors etc.’

Some patients commented that they had considered treatment abroad due to costs relating to donation. The HFEA only regulates treatments performed at UK licensed centres, regulations will vary in other countries.

‘If I were to have treatment again, I would most definitely go abroad and use donor eggs. The cost overseas is far less than the cost of treatment in the UK.’

“It's more expensive [in the UK] than abroad and donor embryos less readily available.”

The recently launched Women’s Health Strategy outlines plans to improve equality in access to treatment. Additionally NICE guidelines are currently under review, with a plan to address issues around equality in their update.

4. Donor eggs can increase birth rates for older patients

As birth rates decline with age when patients use their own eggs, patients in some age groups can increase their chances of having a baby by using donor eggs. In 2018/19, the birth rate per embryo transferred for patients aged 18-34 using their own eggs was 33%, compared to 5% for patients aged 43-50 (Figure 5). However, birth rates remained above 30% for all ages when donor eggs were used.

When using donor eggs, the chance of pregnancy is largely dependent on the egg donor’s age rather than the patient’s. Birth rates can be higher when using donor eggs as egg donors are typically younger (average age of 31) than the IVF patients using them (41), and egg donors are unlikely to have fertility issues. However, despite increasing chances of live birth among older patients, deciding to use donor eggs can be a difficult decision. See our website for more information on what you should consider before using donation.

Figure 5. IVF birth rates above 30% for all ages where donor eggs are used

IVF births per embryo transferred by age and egg source, 2018-2019

Note figure 5: This data includes IVF treatment cycles begun with the intention of having a live birth only. Treatments in which a pregnancy was recorded and no outcome recorded have been excluded. PGT-A and PGT-M treatments have been excluded.

Download the underlying data for Figure 5 as Excel Worksheet

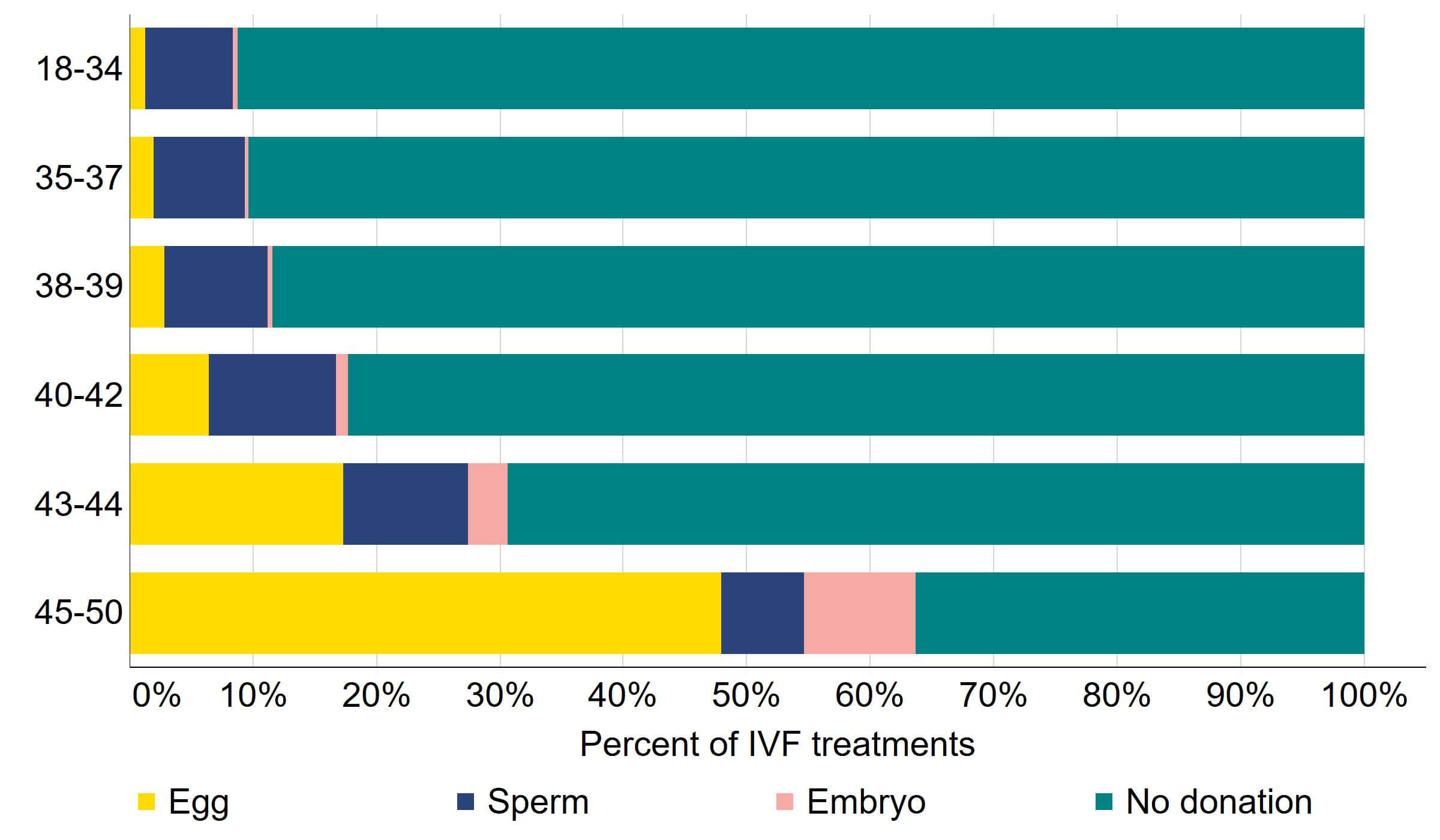

Patients aged 45-50 used donor eggs more than in other age groups, with nearly half of all IVF treatments in this age range using donor eggs in 2020 (Figure 6). In contrast, only 1% of patients aged 18-35 had treatment with egg donation in 2020.

Younger patients largely use donor eggs for medical reasons such as early menopause or genetic diseases. Among patients aged 40 and over, donor eggs are commonly used as birth rates using a patient’s own eggs decrease with age, and this may be their only chance of conceiving a child. While birth rates using their own eggs were similar for patients aged 43-44 (5%) and 45-50 (4%), patients aged 45-50 were nearly three times as likely to use donor eggs.

Patients in female same-sex relationships accounted for 35% of IVF cycles using donor sperm and single patients accounted for 20% of IVF cycles using donor sperm from 2016-2020. The remaining 44% were patients in heterosexual relationships.

Figure 6. Donation most used by patients 45-50

Percent of IVF treatments using egg, sperm, or embryo donation by patient age, 2016-2020

Note figure 6: This data includes IVF treatment cycles begun with the intention of having a live birth only.

Download the underlying data for Figure 6 as Excel Worksheet

5. From 2023, donor-conceived people will be able to access information on their donors

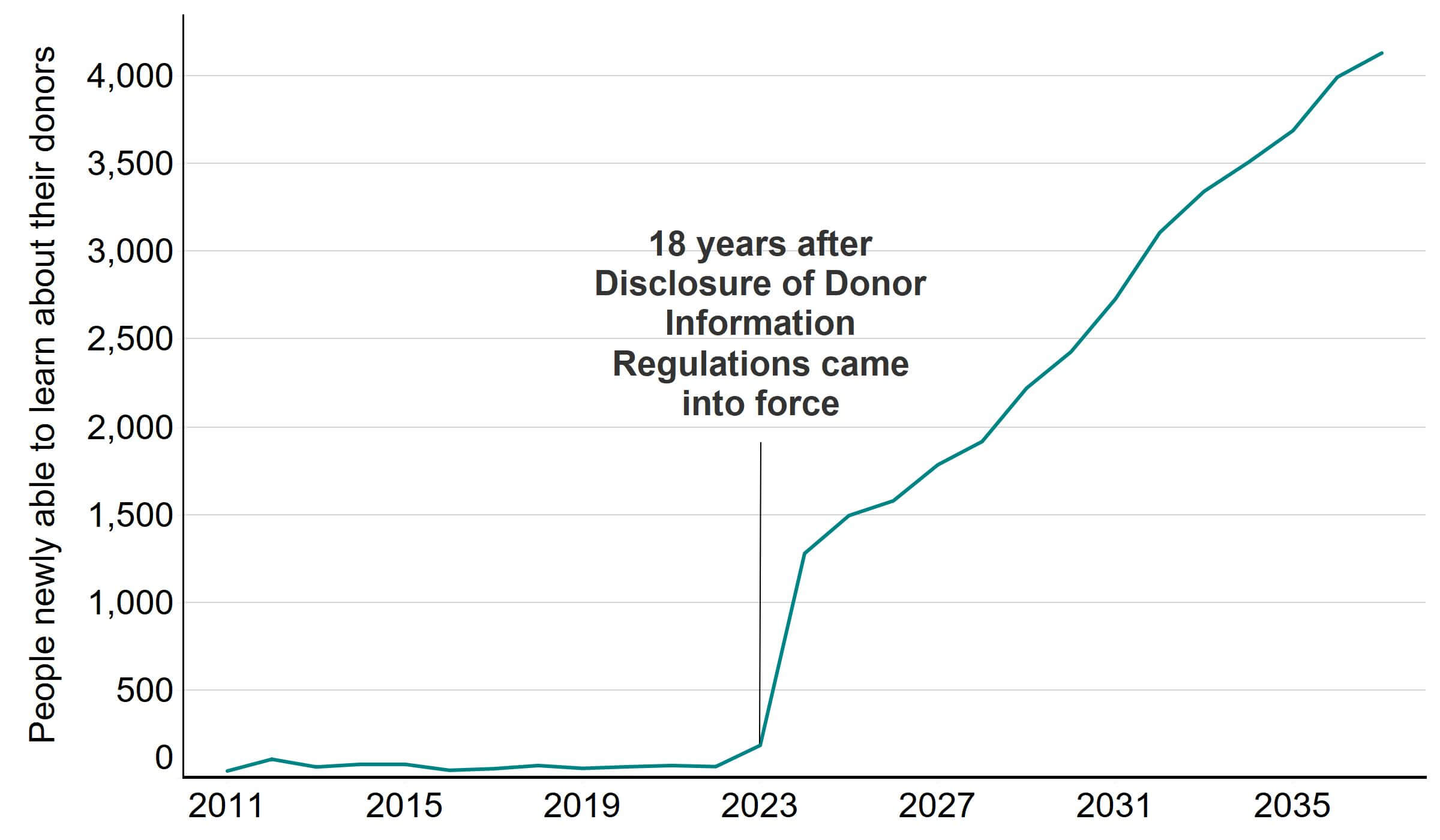

The number of donor-conceived people in the UK newly eligible to request identifying information about their donor will rise from around 70 in 2022 to a maximum of almost 1,300 in 2024 (Figure 7). In total, at the end of 2022 around 800 donor-conceived people will be eligible to request this information, and this is estimated to almost triple to around 2,300 at the end of 2024.

This is due to regulations5 taking effect in 2005 which gave most donor-conceived people the right to access their donor’s information when they turn 18. Most people conceived from an egg, sperm or embryo donation provided on or after 1 April 2005 will be able to submit a request to the HFEA to access some identifying information about their donor such as their name, date of birth and their last known addressII.

People conceived from a donation provided prior to 1 April 2005 can only access identifying information about their donor from age 18 if their donor has voluntarily re-registered to become identifiable. As of November 2022, 260 donors have voluntarily removed their anonymity (113 egg and 147 sperm donors). Around 1,600 people will be able to access information about their donors due to them voluntarily removing their anonymity, around 800 of whom will be aged over 18 by the end of 2022. Of these eligible donor-conceived people, 28 have already applied for and received this information from the HFEA.

Figure 7. Donor-conceived people able to learn about their donors soon to increase

Donor-conceived people turning 18 born to identifiable donors, 2011-2037

Note figure 7: This data includes all births as a result of IVF or DI in which an identifiable sperm or egg donor was used. Details of how donors were determined to be identifiable can be found in the Quality and methodology report.

Download the underlying data for Figure 7 as Excel Worksheet

Parents of donor-conceived children aged under 16 and donor-conceived children aged 16 and 17 were also given the right to access some basic characteristic information about donors used from 1 April 2005. Additionally, donors will be able to find out the number of children born as a result of their donation, their sex, and their birth year. See our webpage for more on the rules around releasing donor information.

The HFEA has so far responded to around 800 requests for non-identifying information from donors, donor-conceived people or their families in 2022. Around a third of requests came from donors for information on children conceived as a result of their donation(s), and two-thirds from donor-conceived children or their parents about donors used in treatment. To learn how to request this information, see our webpage.

In our National Patient Survey, some patients were happy that their children would have access to this information when they become 18.

‘We were much happier using a UK clinic that uses UK eggs donors where our child (and maybe children) will have access to information / the possibility of meeting one day; this feels much better to us. It was a huge leap for us to use donor eggs, but this more open, transparent approach feels better…’

‘I am pleased that my child/ren will have access to their egg donors contact information in the future because its so important for DCPs to have the option to explore their identity.’

However, several patients felt current rules around donor anonymity were too restrictive. These patients mentioned wanting to tell their children more about their donors at an earlier stage, with some wanting direct contact with donors.

‘I now believe that Donor Conceived People have the right to more information about the people they are biologically related to from a much earlier age than those currently set by the HFEA.’

‘I would like to see some mechanism for putting donors and RPs [recipient parents] in contact earlier than 18 if both parties are agreeable.’

The HFEA is currently preparing proposals on potential changes to the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Act 1990 which it will submit to the Department of Health and Social Care. This will include considerations relating to the interactions between donors and families in future. For more information visit the HFEA website.

6. Characteristics of egg and sperm donors have changed over time

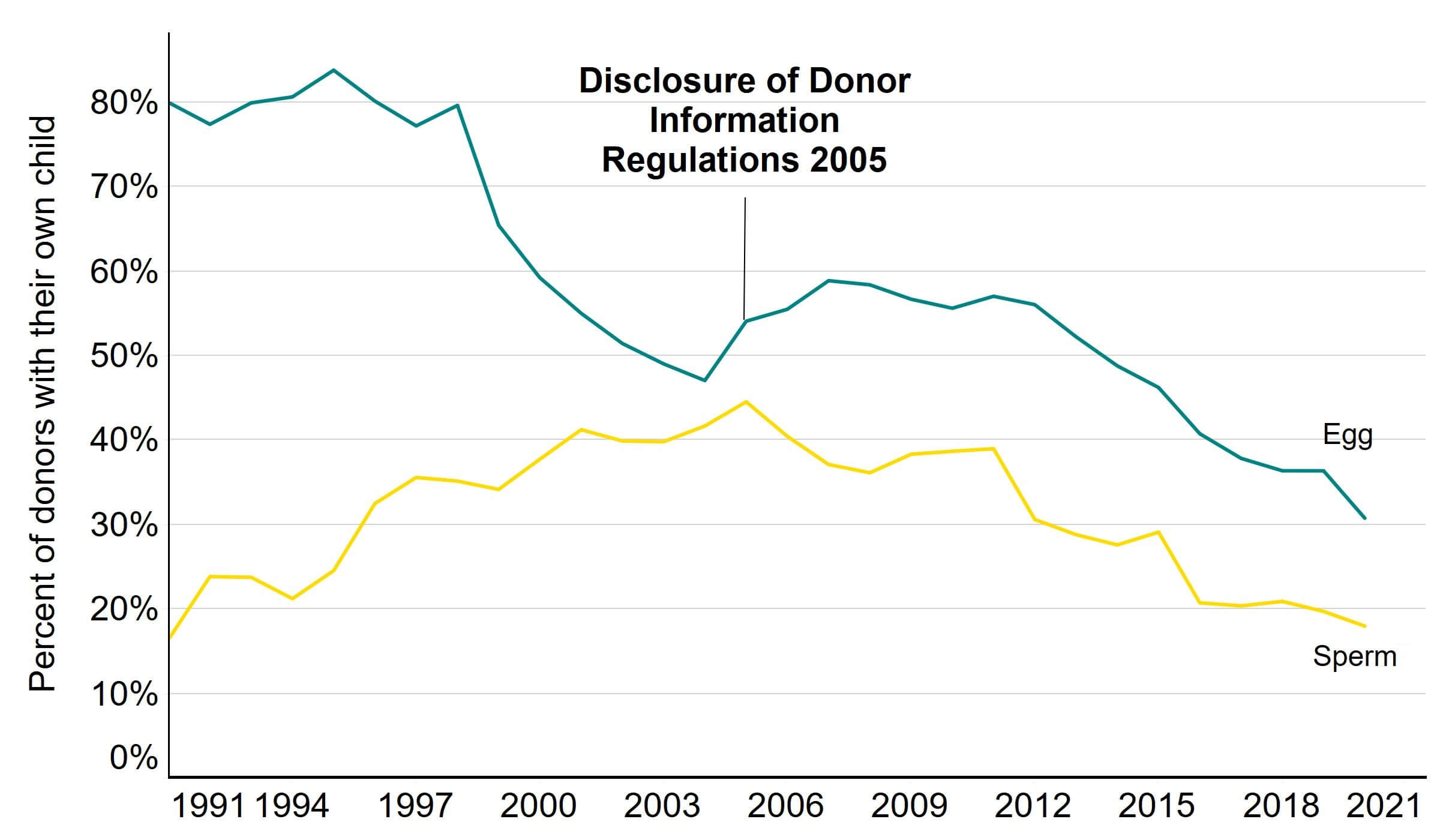

Sperm donor age has increased from a median age of 29 in the 1990s to 33 in the 2010s. UK sperm donors were typically older with a median age of 36 compared to imported sperm donors at a median age of 27 from 2011-2020. Egg donors had a consistent median age of 31-32 from 1991-2020. Current professional guidelines require sperm donors to be aged 18-45, while egg donors should be aged 18-35.

Egg donors more commonly lived with a partner compared to sperm donors, though this has decreased. Around 83% of egg donors lived with a partner in 2010, compared to 48% in 2020. For sperm donors, 57% lived with a partner in 2010 and 39% in 2020.

Donors who had their own child at the time of donation has decreased since 2005 (Figure 8). Around half of donors (54% egg, 45% sperm) had their own child in 2005 and this decreased to 1 in 3 egg donors (31%) and 1 in 5 sperm donors (18%) in 2020. The variation in donors having their own child over time may be due in part to changing criteria in clinic recruitment campaigns, as well as the introduction of the 2005 regulations that removed donor anonymity.

More data on donors is available in the underlying data.

Figure 8. Fewer donors had own children

Percent of new donors with their own child, 1991-2020

Note figure 8: This data uses new sperm donor registrations only. Donors that registered multiple times will only be counted in the year of their first registration.

Download the underlying data for Figure 8 as Excel Worksheet

Sperm donors in England lived in more affluent socio-economic areasIII on average than the general population from 2011-2020 (Figure 9), and egg donors lived in comparable areas to the general population (Figure 10). Fewer sperm and egg donors lived in the most deprived category than the general population.

It is illegal to pay for donation in the UK. Egg donors receive £750 compensation for a donation, while sperm donors receive £35. Previous research studies and Figure 9 and 10 suggest altruism, rather than finances, as the primary motivation for egg and sperm donation in the UK9-10.

Donors were more commonly from deprived areas if they were younger, had overseas passports, or were from ethnic minority backgrounds. This follows wider trends11-12. Egg sharers, patients who donate eggs as part of a scheme to have a lower cost for their own IVF treatment, tended to live in less deprived areas than other egg donors. Further information is available in the underlying dataset.

We are unable to comment on these trends for Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales with any certainty due to small numbers.

Figure 9. Sperm donors more commonly lived in affluent areas

Percentage of new sperm donor registrations in England in each deprivation decile, 2011-2020

Note figure 9: This data includes sperm donors aged 18-45 registering for the first time from 2011-2020 in England. Deprivation levels as in 2015 were usedIII.

Download the underlying data for Figure 9 as Excel Worksheet

Figure 10. Egg donors lived in comparable areas to the general population

Percentage of new egg donor registrations in England in each deprivation decile, 2011-2020

Note figure 10: This data includes egg donors aged 18-35 registering for the first time from 2011-2020 in England. Deprivation levels as in 2015 were usedIII.

Download the underlying data for Figure 10 as Excel Worksheet

About our data

Register data

The information that we publish is a snapshot of data provided to us by licensed clinics, covering 1991-2020. The figures supplied in this report are from our data warehouse containing Register data as at 28/08/2021. We have excluded approximately 2,400 cycles due to technical issues at one centre in England that resulted in reporting errors. Results are published according to the year in which the cycle was started. Due to rounding, some percentages may not add to 100%.

IVF treatments using donor embryos or a combination of donor eggs and donor sperm were combined throughout the report. We estimate from our records that a minimum of 2% of births from two donors relate to embryos donated by a couple (at least 44 births from 1991-2019), compared with a maximum of 98% using separately donated eggs and sperm. Please note that when an embryo is donated, two donor registrations will be submitted, one from an egg donor and one from a sperm donor. As such, embryo donor registrations will be implicitly involved in both egg and sperm donor registrations.

This report uses unvalidated treatment data for 2020 and outcome data for 2019. This is because the HFEA has recently launched a new data submission system for clinics and migrated our fertility treatment and outcomes data to a new database. This data migration has resulted in delays which have prevented the use of 2020 outcome data, or the validation of the 2020 treatment data.

For further information, please see our Quality and methodology report and information page in the underlying dataset.

Patient survey data

We received a total of 1,868 responses. Once partial completes and screened-out responses had been removed, a total of 1,233 patient were included in the analysis. This survey was the source of all quotations from patients used in this report.

The survey was conducted between 2 November – 7 December 2021 and was open to anyone who had undergone fertility treatment in the UK in the past ten years, including patients, partners, intended parents and surrogates. In the report we refer to survey respondents as patients throughout as this covers 95% of respondents.

The survey is broadly representative of the fertility patient population, with a few exceptions. More details can be found in the survey quality and methodology report.

Additional information

See the underlying data of this report for more information, including:

- Number of children conceived from egg, sperm and embryo donation per year.

- Funding of treatments using donor eggs, sperm and embryos by region and partner type.

- Characteristics of egg and sperm donors, including exploration of the index of multiple deprivation.

Footnotes

- There is considerable national variation in this figure. In Scotland, 57% of DI treatments undertaken by single patients and patients in female same-sex relationships received NHS funding, while in England this value was under 3%. NICE are currently revaluating their guidelines around fertility treatment funding in England.

- Some exceptions to this exist, such as if a patient already had a child conceived using an anonymous donor prior to 1 April 2005, and they wanted to conceive a second child using a donation from the same donor after this date. These exceptions were not accounted for in the estimates of this section. For details, see the Quality and methodology report and our website.

- Deprivation and affluence in this report refer to the Indices of Multiple Deprivation. Donor postcodes have been matched against these local area indices, as calculated by the Department for Levelling Up, Housing & Communities.

About the HFEA

The HFEA is the UK’s independent regulator of fertility treatment and research using human embryos. Set up in 1990 by the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Act, the HFEA is responsible for licensing, monitoring, and inspecting fertility clinics – and taking enforcement action where necessary – to ensure everyone accessing fertility treatment receives high quality care.

The HFEA is an ‘arm’s length body’ of the Department for Health and Social Care, working independently from Government providing free, clear, and impartial information about fertility treatment, clinics and egg, sperm and embryo donation.

The HFEA collects and verifies data on all treatments that take place in UK licensed clinics which can support scientific developments and research and service planning and delivery.

The HFEA is funded by licence fees, IVF treatment fees and a grant from UK central government. For more information visit, hfea.gov.uk.

Contact us regarding this publication

Media: press.office@hfea.gov.uk

Statistical: intelligenceteam@hfea.gov.uk

Accessibility: comms@hfea.gov.uk

Notes on Trends in egg, sperm and embryo donation 2020

- Intracytoplasmic sperm injection. Survey of world results, Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 2000, 900: 336-344

- Trends in the use of intracytoplasmatic sperm injection marked variability between countries, Human Reproduction Update, 2008, 14: 593-604

- Equality Act 2006

- Human Fertilisation and Embryology Act 2008

- The Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority (Disclosure of Donor Information) Regulations 2004 (legislation.gov.uk)

- Reconsidering the number of offspring per gamete donor in the Dutch open-identity system, Human Fertility, 2011, 14: 106-14

- Assisted Conception and South Asian communities in the UK: public perceptions of the use of donor gametes in infertility treatment, Human Fertility, 2013, 16: 48-53

- Fertility Network UK – NHS Funding

- Being an identity-release donor: a qualitative study exploring the motivations, experiences and future expectations of current UK egg donors, Human Fertility, 2016, 19: 230-241

- Socio-demographic and fertility-related characteristics and motivations of oocyte donors in eleven European countries, Human Reproduction, 2014, 29: 1076-1089

- People living in deprived neighbourhoods - GOV.UK Ethnicity facts and figures (ethnicity-facts-figures.service.gov.uk)

- Populations by Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD) decile, England and Wales, 2020 – Office for National Statistics

Review date: 6 April 2025