Overview of HFEA public consultation on law reform 2023

Consultation held February – April 2023 on reforming the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Act

Published: November 2023

Download the underlying figure dataset as .xlsx

Table of contents

- Introduction

- Overview of response groups

- Summary of responses by consultation theme

- Overview of responses

- Individual respondent demographics

- Methodology

- List of organisations that responded to the consultation

Introduction

The Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority (HFEA) has been calling for an update to the fertility law in the UK and has made a wide range of proposals that we believe would improve patient care and maintain our position as a country where scientific and clinical innovation can flourish. As part of the process for developing these recommendations, the HFEA sought the views of patients, clinic staff and others interested in the area via a public consultation.

The launch of the consultation gained substantial interest from the media, particularly in relation to the areas of proposed changes to recognise new scientific developments and release of donor anonymity.

We received a wide range of responses from many organisations; those affected by fertility treatment including patients and partners, parents of donor-conceived individuals, donor-conceived individuals themselves, and donors and others; professional staff working in fertility clinics; academics; lawyers; researchers; and interested members of the public.

The range of views submitted to the consultation were extremely helpful in understanding the degree of support for our thinking and in helping us to develop those proposals into their final recommendations as set out in the separate report.

There was support for the majority of the HFEA proposals across respondents and this is summarised in more detail below. There were some responses from some organised campaigns, for example, those who are opposed to embryo research. There were also some detailed responses from organisations who did not support the proposals.

The HFEA would like to thank every individual and organisation who took the time to respond to our consultation. Each response has been read in detail and helped to contribute to what, we hope, will in time be an updated law, relevant for the modern fertility sector.

Overview of response groups

A total of 6,803 responses were included in the analysis (Table 1)1. The methodology for data collection and analysis can be found in the Methodology section of this annex.

Respondents were able to share:

- views on behalf of an organisation

- their professional views

- both their professional and personal views (i.e. they work in the fertility sector but have also been a patient or partner of a patient)

- their personal views and experiences

As there were large differences in responses between those who gave personal views as interested members of the public and those who gave personal views as patients, partners or others who were directly or indirectly involved in fertility treatment, we present the results by five response groups in this report:

- Organisations

- Professionals

- Professionals and patients (denoted as professional/patient throughout)

- Patients (including partners, intended parents, donor-conceived individuals, donors and surrogates)

- Interested members of the public (denoted as ‘members of the public’ throughout)

We received 61 (1%) responses from organisations. All questions were optional and for most questions, at least a third of organisations did not provide a response. This is likely due to organisations choosing to only answer the questions most directly related to their area of expertise or interest. A list of the organisations that responded to the consultation is available in the List of organisations that responded to the consultation section of this annex.

Just under 5% (265) of responses were from individuals sharing their professional views and experiences, which included, for example, healthcare professionals from licensed clinics and researchers (professional response group). Professionals who had been involved in treatment themselves and responded to the consultation in both a patient and professional capacity made up 2% (127) of submissions (professional/patient response group).

Just over 12% (828) of the submissions came from individuals sharing their personal views and experiences, including current and past patients, partners or other family members and friends; donors and donor-conceived individuals; parents of a donor-conceived individual; surrogates; and intended parents (patient response group). The details of individual respondents can be found in the Individual respondent demographics section of this annex.

A significant proportion of responses came from members of the public (over 80% of total responses). However over 90% of these respondents did not answer most questions and in such cases, it was difficult to draw any conclusions for this group. Free text responses indicated that the questions that were answered by this group largely reflected an organised response reflecting wider opposition to the use of human embryos in research.

| Table 1. Number of responses by group | ||

|---|---|---|

| Response group | Number of responses | Percentage |

| Organisation | 61 | 1% |

| Professional | 265 | 4% |

| Professional/patient | 127 | 2% |

| Patient | 828 | 12% |

| Members of the public | 5,522 | 81% |

| Total | 6,803 | 100% |

Summary of responses by consultation theme

Section 1 – Patient safety and promoting good practice

This section set out eight proposals to promote patient safety and good practice, covering four key areas. There was general agreement with the proposal for greater flexibility in the inspection regime with support for risk-based inspections and decreased inspection frequency for consistently compliant clinics. Responses from organisations were mixed for this proposal and free text responses indicated some concerns about reduced oversight and the need for a minimum frequency of inspections.

There was support for the proposal for more flexibility in the appointment of clinic leaders, such as a deputy Person Responsible (PR), to facilitate the delivery of high-quality care. Free text responses noted that appointing deputy PRs could facilitate sharing responsibility, knowledge and experience.

Support was evident across all response groups for the proposal for broader regulatory tools to tackle poor patient care. Free text responses across response groups highlighted that broader powers would enable proportionate responses to non-compliances. The proposed use of financial penalties to bring the HFEA in line with other regulators was supported, although some concerns were raised on whether this may disproportionately impact smaller/NHS clinics and patients. Support for proposed regulation of services outside of clinics was underpinned by concerns about patient safety and fraud. Some organisations and professionals highlighted a need for clarity of what services outside of clinics may fall within the HFEA’s remit. Patients were most strongly in support of proposals to broaden powers to tackle non-compliances and there being an explicit duty for HFEA and clinics to act to promote patient care and protection.

There was general support for the proposal to make licensing decisions more efficient. Free text responses reiterated support for changes in the current appeals process as long as effectiveness is maintained. Flexibility to set standard licence conditions was endorsed to enable the HFEA to bring about changes across the sector when needed, with some organisations and professionals calling for more clarity on the proposed changes to setting standard licensing conditions.

Section 2 – Access to donor information

This section set out three proposals that focused on aspects of information provision relating to donor treatment. Respondents were generally supportive of the proposal to require clinics by law to inform donors and recipients of potential donor identification through DNA testing websites. Free text responses highlighted the rapidly evolving field of genetic testing and suggested broader language in any changed legislation about the routes of identification to future proof the Act.

There was a varied response for the proposal to amend the Act for a dual track system to provide parental and donor choice to opt for anonymity until age 18 or identifiable information after the birth of a child across the response groups. Free text responses indicated that there is support for future legislation to move towards removing anonymity. However, the proposed dual track system was considered unsuitable by many as there were concerns it could create complexities and disparity in information provision. The importance of access to information about donor siblings was also highlighted.

There was broad support for mandatory implications counselling before starting donor treatment across all response groups. Free text responses highlighted the importance of this to ensure long term considerations were discussed prior to treatment.

Section 3 - Consent

This section set out three proposals relating to different aspects of consent. There was a mixed response to the proposal to simplify the current consent regime in ways that continue to provide protection to patients. The free text responses provided insight into the varying responses. While there was support for simplifying the consent regime, the proposed ‘opt out’ model was not considered to be necessarily suitable due to the complexities of consent for fertility treatment and storage and use of eggs, sperm, and embryos. However, there was no consensus on an alternative model from the free text responses.

There was support for the proposal to ensure the sharing of fertility patient data in a non-fertility medical setting is aligned with the current regulations for the sharing of other patient/medical data between healthcare providers. Free text responses highlighted that sharing data can facilitate patient safety across healthcare providers.

There was support from most response groups for the proposal for consent for donating embryos to be extended to allow patients to give consent to research embryo banking. Free text responses highlighted that the current process to donate embryos to research can include several barriers. Many agreed that an embryo bank may reduce some barriers, such as fertility clinics needing to be linked with specific research projects. Free text responses indicated that disagreement to the proposal from members of the public reflected broader objection to the use of human embryos in research.

Section 4 - Scientific developments

This section set out proposals relating to the future regulation of scientific innovation. Most response groups supported the proposal for the Act to explicitly give the HFEA greater discretion to support innovation in treatment. Free text responses indicated that support for greater discretion was underpinned by the appreciation that scientific development in this area is rapidly evolving and that the use of regulatory ‘sandboxes’, or similar mechanisms, could be a useful tool to facilitate innovation.

Across most response groups, there was support for proposed changes to be made to the Act to allow regulations to be made to enable future revisions. Free text responses highlighted the importance of parliamentary and public debate and oversight of decisions about scientific developments. It was also noted that collaboration with organisations, experts, and other key stakeholders may support the implementation of regulations to enable future revisions.

Free text responses for both proposals indicated that the disagreement from members of the public reflected broader objection to the use of human embryos in research.

Overview of responses

Section 1: Patient safety and promoting good practice

In total, 1,557 responses were received for this section (Table 2), which included eight questions and 272 free text responses.

| Table 2. Total number of responses by response group for Section 1: Patient safety and promoting good practice. | ||

|---|---|---|

| Response group | Number of responses | Percentage |

| Organisation | 41 | 3% |

| Professional | 228 | 15% |

| Professional/patient | 111 | 7% |

| Patient | 696 | 45% |

| Members of the public | 481 | 31% |

| Total | 1,557 | 100% |

Question 1 – Better patient care through risk-based inspection and licensing

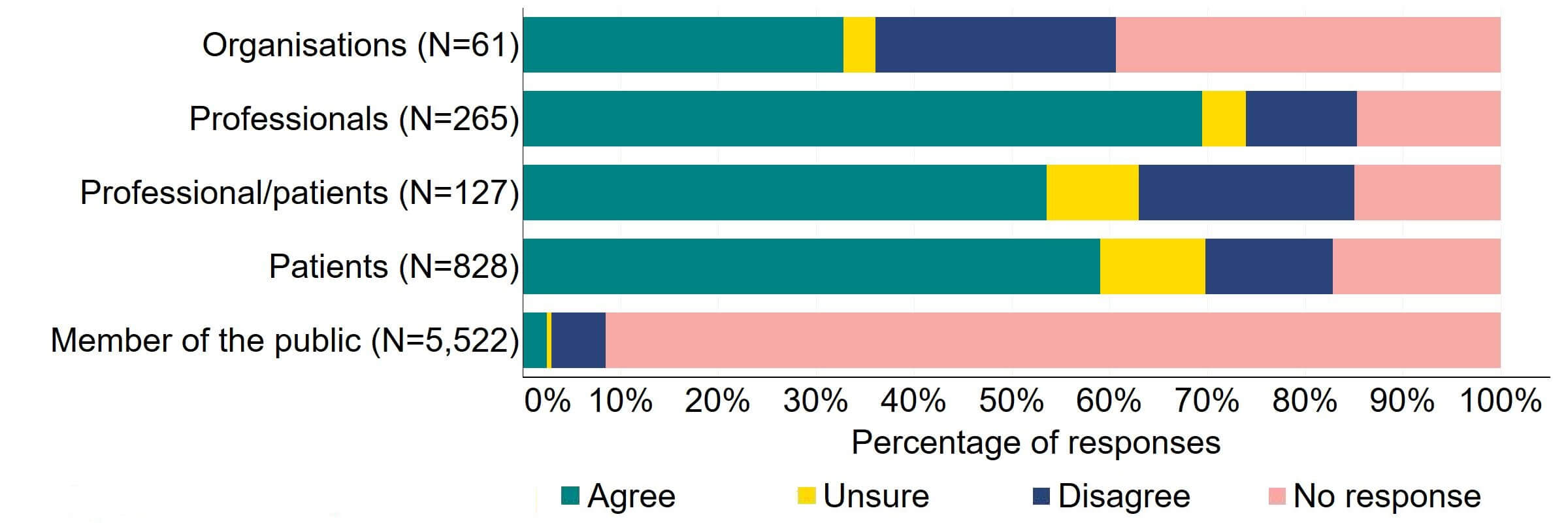

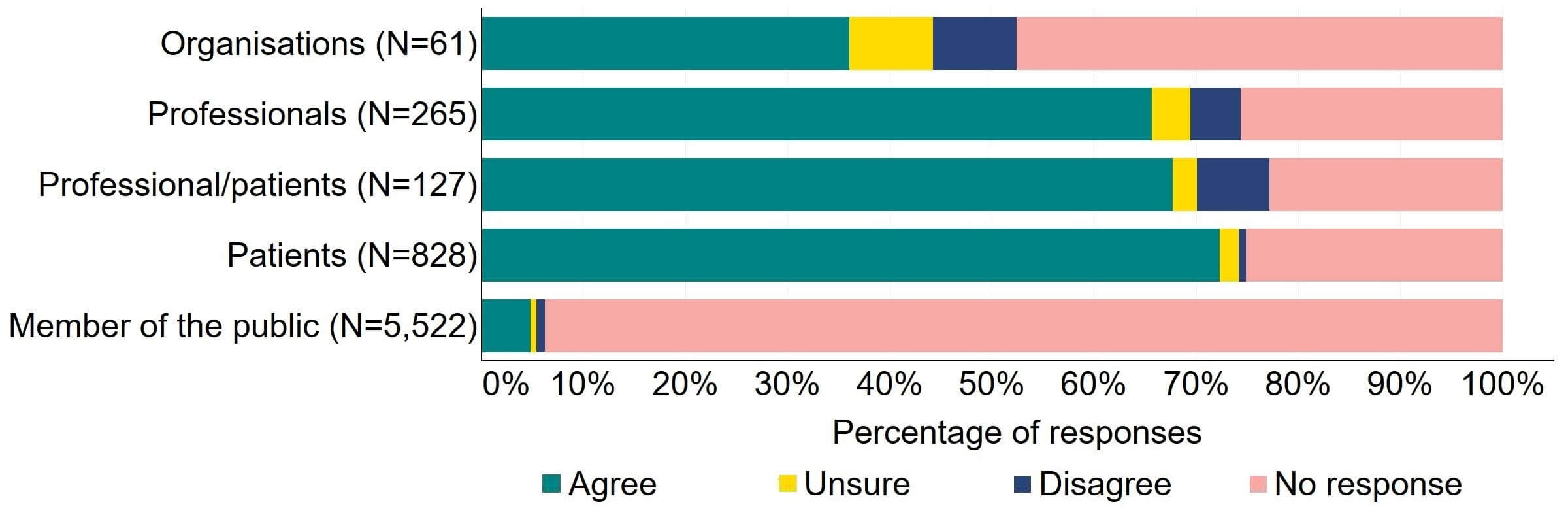

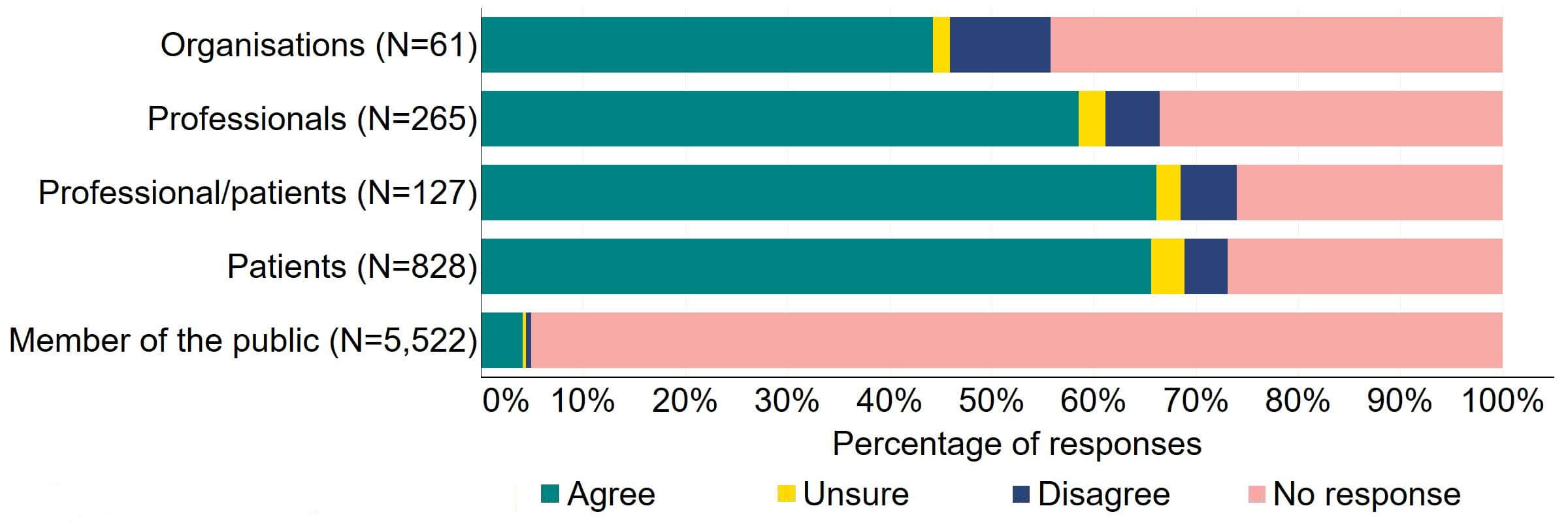

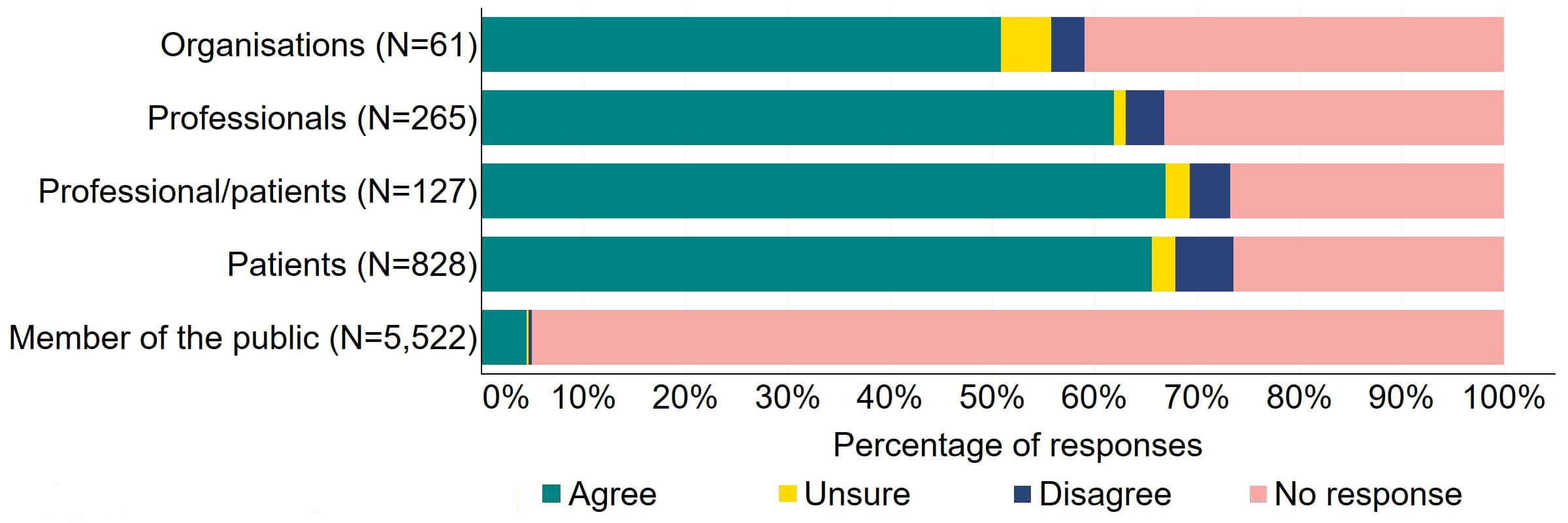

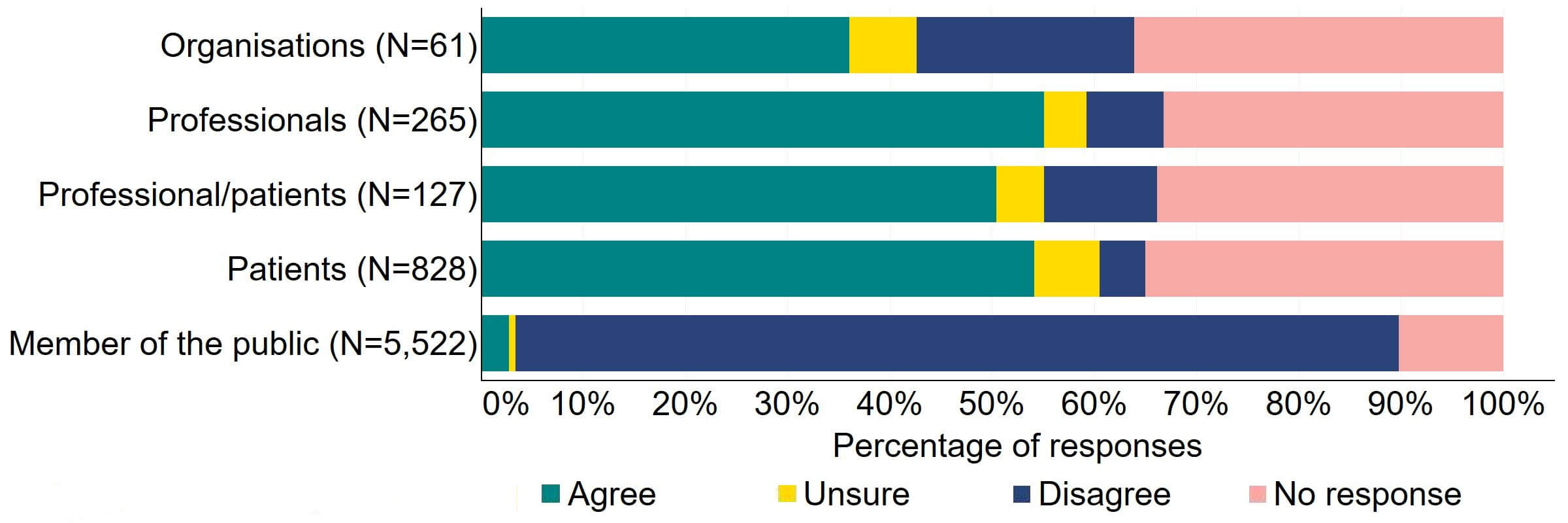

There was agreement from most of the individual respondent groups that the HFEA should have greater freedom to vary its inspection regime (Figure 1). The responses from organisations were varied, with one third (20) agreeing and a quarter (15) disagreeing. Professional responses had the highest level of support with around 70% (184) agreeing with the proposal. Just under a quarter (28) of professional/patient responses disagreed.

Figure 1. To what extent do you agree or disagree that the HFEA should have greater freedom to vary its inspection regime?2

Overall, the theme from the free text responses that referred to this proposal indicated support for inspection regime flexibility and, although it was felt that inspection time frames could be widened for compliant clinics, some respondents suggested that a minimum frequency of inspections should be kept.

Reasons for support included relieving pressure on compliant clinics by reducing administrative burdens and encouraging compliance:

‘It is appropriate for the HFEA to have greater flexibility for inspecting clinics that are deemed to be low risk. Such an approach could encourage compliance and thus reduce the burden for clinics’ [British Fertility Society]

There was also support for risk-based and desk-based inspections to play a role in inspection regime flexibility, noting that risk-based inspections are consistent with other regulators. Although inspection regime flexibility was supported, organisational and professional responses indicated that a minimum frequency should be retained. Other responses suggested that inspections should be triggered by changes in staffing or treatments offered:

‘I think that inspections should still be regular, although for outstanding clinics perhaps 3 years might be appropriate. If anything changes e.g. staffing/PR/treatment offered then that should bring on another inspection.’ [Professional – A group, organisation, or charity representing patients or others]

Some responses referenced flexibility to the inspection regime for research centres. These responses were generally supportive of increased flexibility, particularly noting that research licences do not always align with funding or project durations.

Some organisations and professionals did not support greater flexibility on inspections citing concerns about reduced oversight and that standards may fall:

‘We recognise the pressures related to inspection and the need to ensure that inspection is proportionate, balancing costs, maintaining quality services which adhere to regulations, avoiding unreasonable pressures on agencies and staff and upholding the wider public interest. We would suggest that inspection is an essential safeguard and that, in the private and public sector environments which characterise this sector, a loose touch inspection would result in a fall in standards.’ [Project Group on Assisted Reproduction]

Responses from the patient and members of the public response groups also supported inspection regime flexibility. However, like some organisational and professional responses, these responses detailed some concern that there might not be sufficient oversight of non-compliant clinics and recommended that a time limit should be maintained:

‘I think there should be more flexibility around inspections of clinics and sanctions etc., but I would not want bad clinics to fall through gaps.’ [Patient]

‘The description of proposals for more flexible inspection regime didn’t address the concern that clinics might end up given a free pass for too long after a fully compliant inspection.’ [Patient]

Question 2 – Better supporting clinic leaders to deliver high quality care

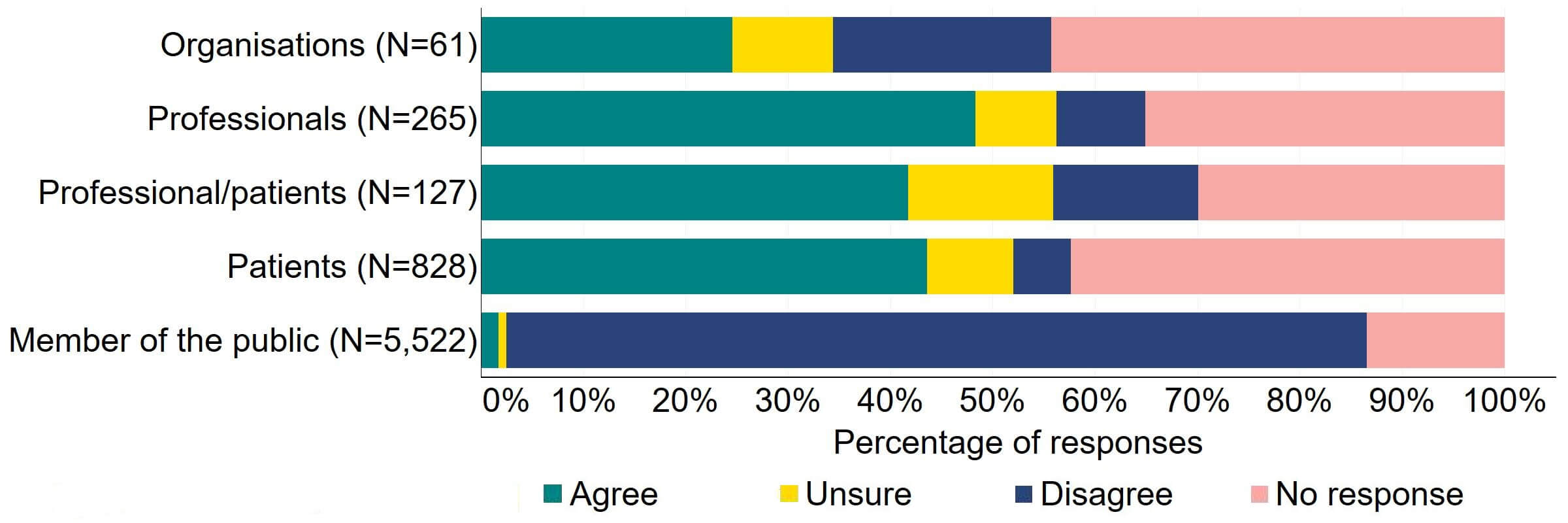

Overall, there was support for more flexibility in the appointment of clinics leaders (Figure 2). Most (20) of the organisations that responded to this question supported this proposed change, with a minority (11%, 7) disagreeing. Professionals had the highest level of support with 68% (181) agreeing, and more than half (60%, 571) of professional/patients and patients agreed with the proposal.

Figure 2. To what extent do you agree or disagree that there should be more flexibility in the appointment of clinic leaders, for example introducing the option of a deputy person responsible (PR), and broadening the criteria for the qualifications and experience required to be a PR?2

Overall, the main theme for responses indicated that proposed changes to the appointment of clinic leaders were welcomed, with some support for deputy PRs, but generally there was limited support for widening the qualification and experience criteria.

Responses from organisations and professionals reflected support for flexibility in the appointment of clinic leaders. Some responses referred to having a multi-disciplinary management team of clinical leaders. It was noted that appointing deputy PRs could facilitate sharing responsibility, knowledge and experience:

‘With regards to deputy PRs - this again is an area where we all strongly agree - not only does it share the responsibility it also brings together extra knowledge and experience especially as many clinics are expanding.’ [Royal College of Nursing]

It was also suggested that the Licence Holder could play a role in governance structure of the clinic:

‘We agree with this and feel that the post of Deputy PR would provide support and advice should the PR not be available for any reason. The Licence Holder post currently has no job description and maybe the three posts together could form a good governance structure.’ [Maternal and Infant Health team, Scottish Government]

Some responses indicated that more clarity on the role of the deputy PR would be needed. A minority of organisational responses disagreed or were uncertain about the appointment of deputy PRs. Some suggested that further changes and options should be considered noting that management and professional accountability may not always align, and alternative accountability models should be explored. A small number of free text responses commented explicitly on the proposal to broaden the criteria for the qualification and experience required to be a PR. Some organisational and professional free text responses indicated limited support or concern for this change, with some suggesting the current requirements for qualifications and experience should be kept:

‘ARCS [Association of Reproductive and Clinical Scientists] believe every licenced treatment and storage site should have a dedicated PR, we believe the current criteria of experience in the field are desirable and this should not be lessened.’ [Association of Reproductive and Clinical Scientists]

There were limited free text responses from the patient and members of the public response groups to this proposal. The small number of responses were generally supportive of the proposal of flexibility in the appointment of clinic leaders including appointing a deputy PR, but limited support for broadening the criteria for qualifications and experience.

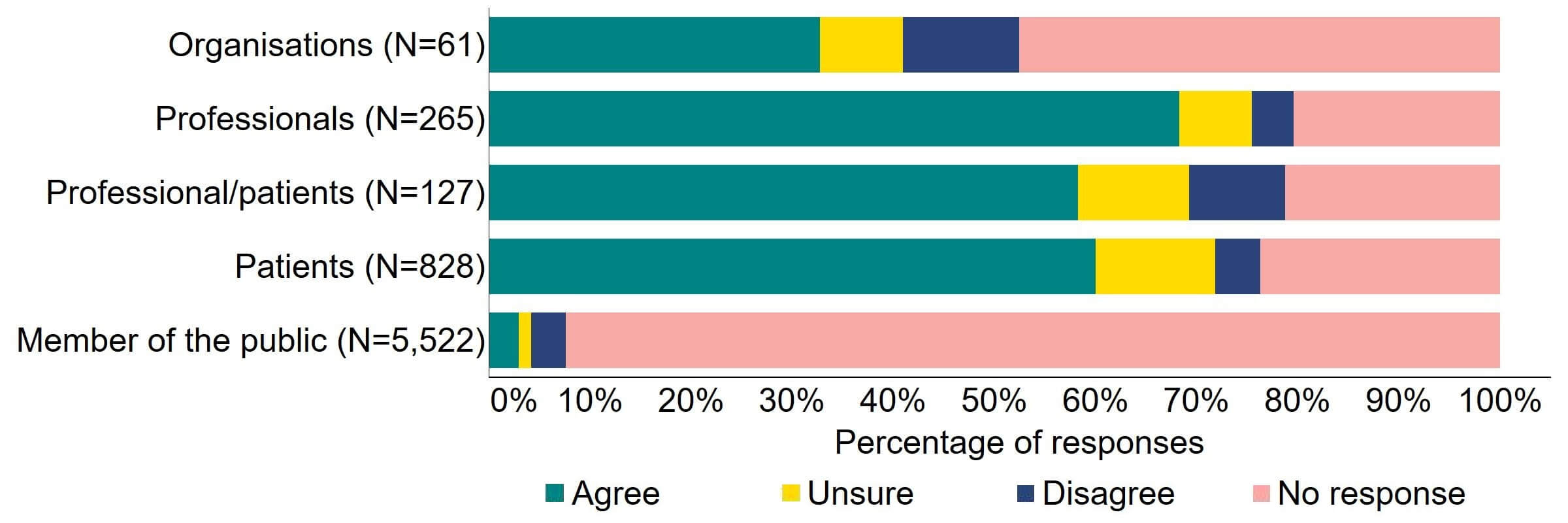

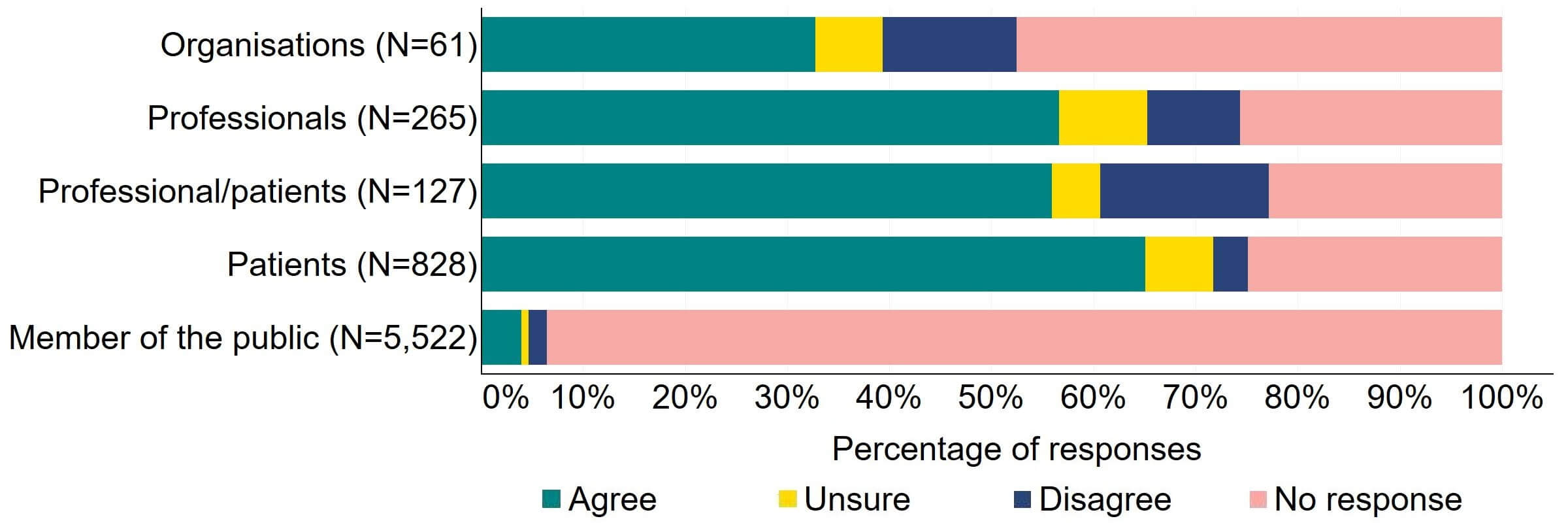

Question 3 – Better regulatory tools to tackle poor patient care

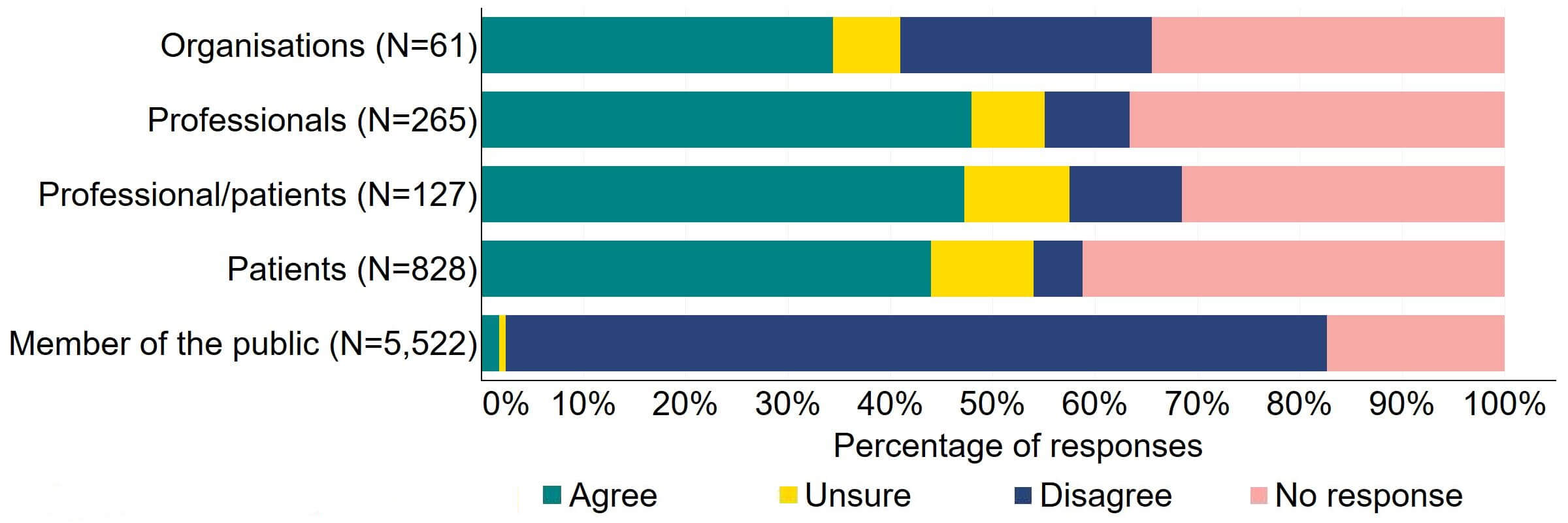

Most responses supported the HFEA having broader, more effective range of powers to tackle non-compliances (Figure 3). Most of the organisations that answered this question (24) agreed with the proposal and 10% (6) disagreed. Most professionals, patients/professionals and patients were supportive of the proposal, with more than half agreeing.

Figure 3. To what extent do you agree or disagree that the HFEA should have a broader, more effective range of powers to tackle non-compliance?2

There were a low number of free text responses that referred to this proposal and these were primarily received from organisations or professionals. Overall, an overarching theme suggested that broadening powers would enable a proportionate response to non-compliances, however a small number of responses perceived that the HFEA already has sufficient power for this.

Some organisational and professional responses referred to support for changes to powers needed to tackle non-compliance in a proportionate way:

‘Additional appropriate sanction options will provide the HFEA with more flexibility rather than simply the suspension or revocation of a licence which can impact patient services. Care would need to be taken to ensure that a licence is still revoked where the issue requires that patient treatment should stop especially in areas in regard to patient safety.’ [Maternal Infant and Health team, Scottish Government]

It was suggested that making more aspects of the Code of Practice directly enforceable would mean the HFEA’s powers would be consistent with other regulators when tackling non-compliance:

‘The CMA [Competition and Markets Authority] is of the view that consideration should be given to making more aspects of the HFEA’s Code of Practice directly enforceable, making compliance with the HFEA’s Code of Practice a standard licence condition, or to incorporating protection of patients’ consumer interests into clinics’ standard licence conditions, to help ensure patients are treated fairly. This would bring the HFEA’s regulatory powers more in line with those of other sector regulators.’ [Competition and Markets Authority]

This was noted by some respondents as particularly important for areas of non-compliance related to counselling and donor information. However, a minority of organisations and professionals responded that the rationale for broadening these powers further was not clear.

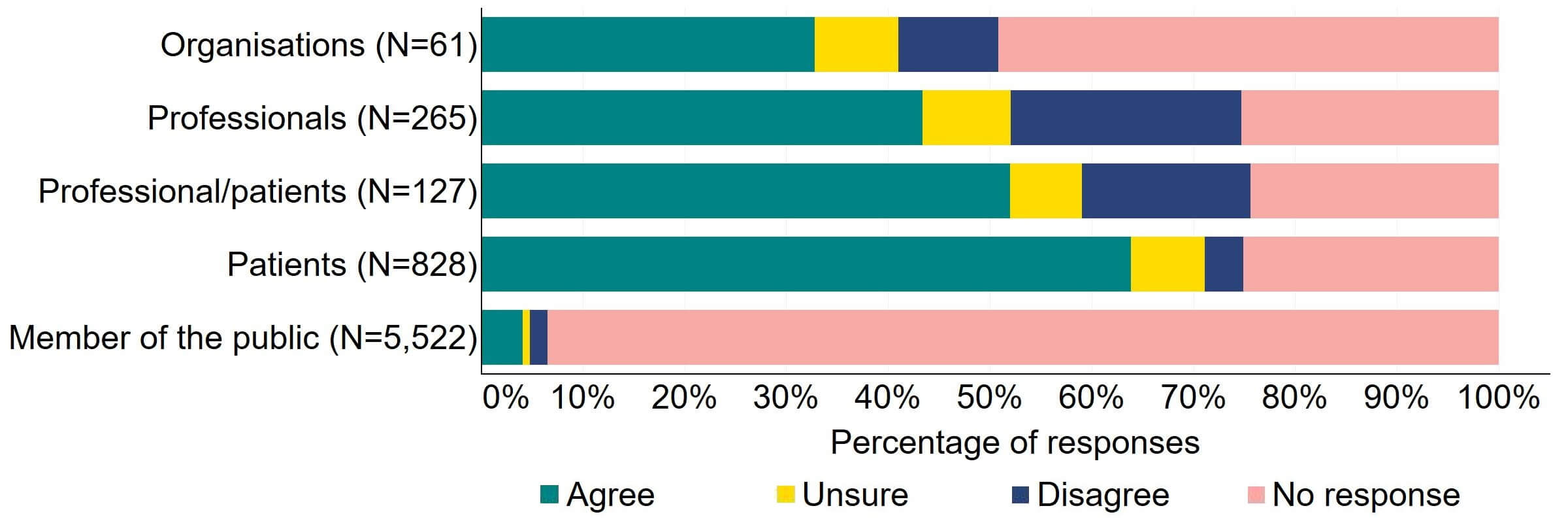

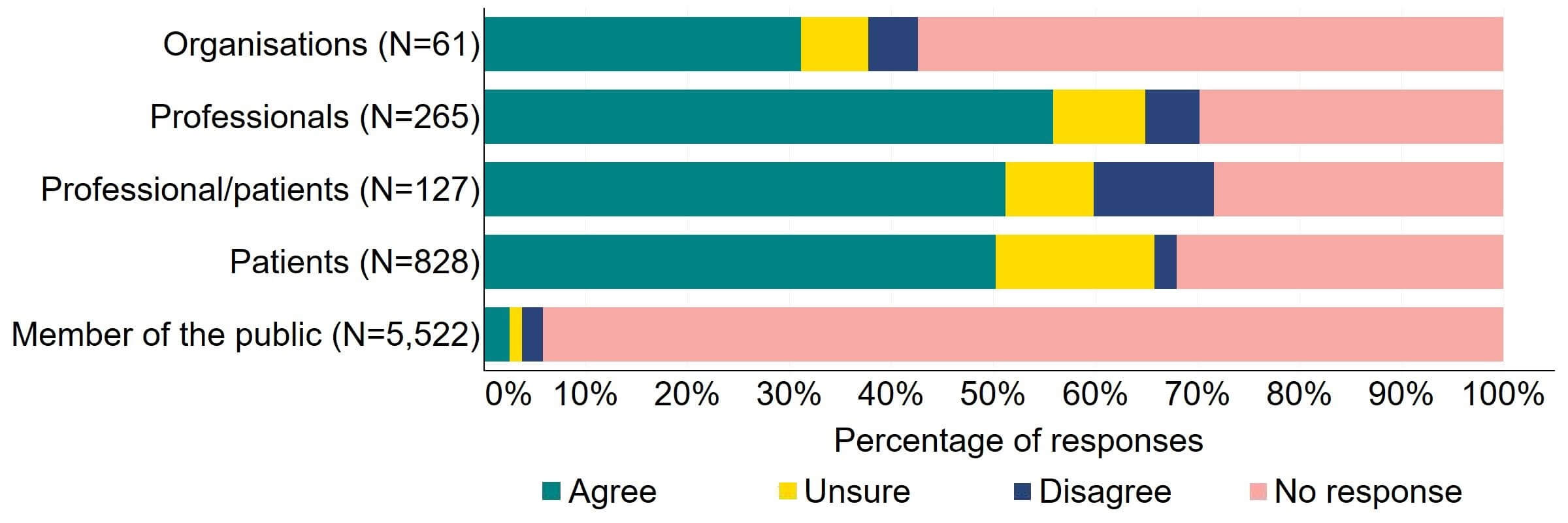

Question 4 – Better regulatory tools to tackle poor patient care

There was support across all response groups for the HFEA to have a broader range of powers to impose financial penalties (Figure 4). Most (20) organisations who gave a response agreed with the proposal. Half of individuals responding from the professional/patient response group provided support. Patients had the most support with nearly 64% (526) agreeing with this proposal. The highest level of disagreement came from professionals with 23% (60) disagreeing.

Figure 4. To what extent do you agree or disagree that the HFEA should have a broader range of powers to impose financial penalties across the sector?2

The overarching view from free text responses that referred to this proposal suggested that financial penalties could play a role in regulation of fertility clinics but there is concern that this would disproportionately impact smaller/NHS clinics and that fines may filter down to patients via increased treatment pricing.

Organisational responses gave some support for financial penalties, for example to bring the HFEA in line with other regulators:

‘The CMA also strongly agrees that the range of sanctions available to the HFEA should include the ability to impose financial sanctions. This would bring the HFEA’s powers in line with those of other sector-specific regulators, such as the CQC [Care Quality Commission], Ofgem [Office of Gas and Electricity Markets], Ofcom [Office of Communications], Ofwat [Office of Water Services], and the Gambling Commission, all of which have the power to impose financial penalties for breach of sector rules or licence conditions.’ [Competition and Markets Authority]

Although, it was noted that this may not always be applicable or appropriate as a stand-alone method to tackle non-compliance, including if patient safety is of concern:

‘ARCS [Association of Reproductive and Clinical Scientists] agree that there should be wider ability for proportionate action. Our SAC [Scientific Advisory Committee] supported in principle the option for financial penalties but noted that this may not always be applicable (i.e. for research licences). In terms of implementation, if the duration of license is amended, one sanction could be time-limited licences/increased frequency of inspection.’ [Association of Reproductive and Clinical Scientists]

Other organisational responses indicated lack of support or uncertainty about the proposal to apply financial penalties suggesting that it was unclear whether financial penalties would result in timely improvements in patient care. A minority implied that further justification for implementation of financial penalties may be needed:

‘The consultation document claims that financial penalties 'would ensure that a clinic would need to improve their standard of care whilst minimally impacting existing patients'. But such penalties do not guarantee that the 'standard of care' will improve quickly, if at all. What is the evidence that fines would serve as a deterrent?’ [Progress Educational Trust]

Some organisational and professional responses indicated that there was general concern that financial penalties would disproportionately impact smaller and/or NHS clinics:

‘I believe [financially] penalising clinics could work - but am concerned about how it would affect NHS and private clinics differently. NHS clinics do not have much control of their own budgets and if receive a financial penalty could suffer further penalties from the Commissioners. I feel it could be unfair on NHS clinics and wouldn't have the desired [e]ffect on private clinics that have greater financial power.’ [Professional - A professional or clinical group or organisation]

It was also highlighted that, independent of whether a response supported the proposal or not, clarity was needed on the types of non-compliances that would be subject to financial penalties. Responses from the professional and patient response groups reflected concerns about financial penalties filtering down to patients (e.g., via increasing fees) or potentially diverting resources away from patient care:

‘Regarding the section about levying fines - I would worry that clinics would push those costs onto patients. Fines need to come out of their profits and not later show up on patient bills.’ [Patient]

‘Financial penalties - I am not sure that financial penalties do promote better patient care. When NHS Trusts are fined for lapses in patient care it does make me think quite the opposite - that there are then fewer resources available to improve patient care, such as buying new equipment, recruiting staff. Perhaps organisations could ring fence certain money and demonstrate to the HFEA how that has been used to improve patient care?’ [Professional - A professional or clinical group or organisation]

Some donor conception support organisations and individuals felt that financial penalties or licence revocations should be applied to UK fertility clinics that may play a role in advising patients to seek donation treatments outside of the UK, however this was beyond the remit of this consultation.

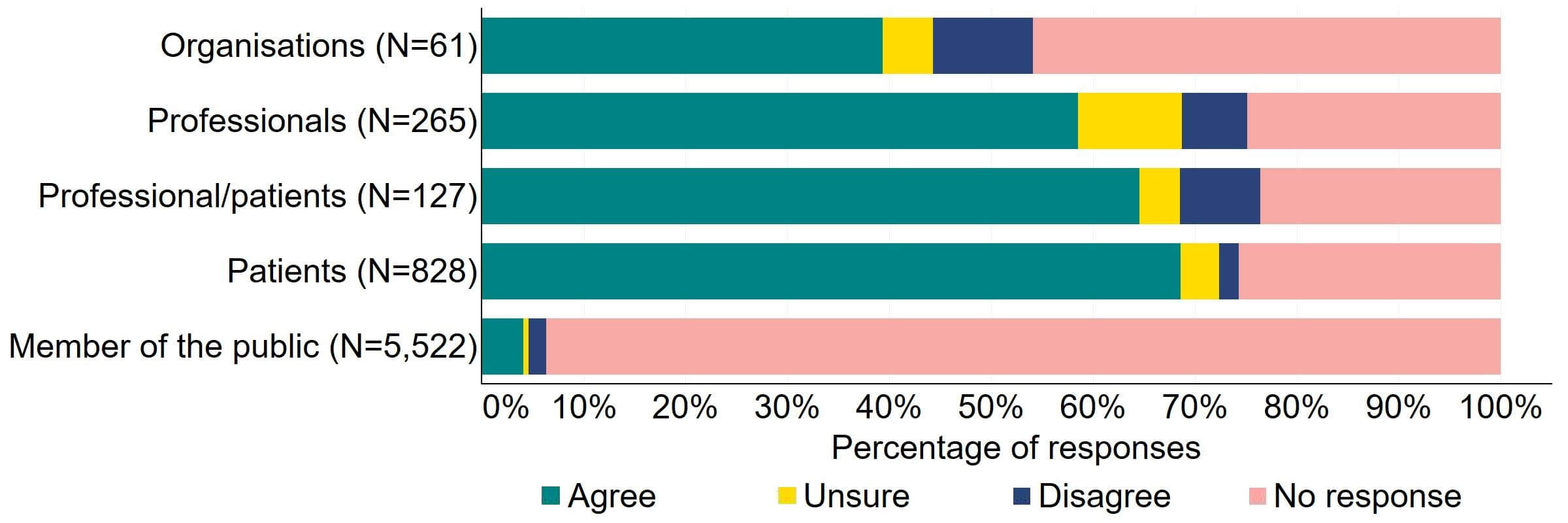

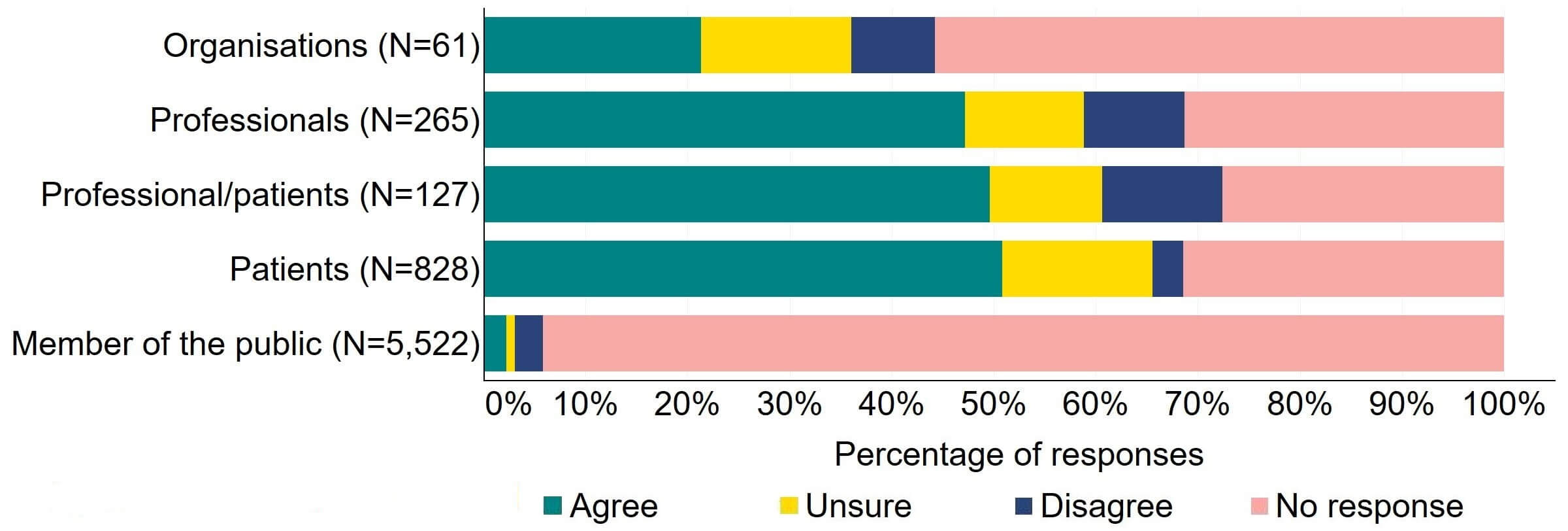

Question 5 - Better regulatory tools to tackle poor patient care

Overall, there was support for an explicit duty on the HFEA and clinics to act to promote patient care and protection (Figure 5). Most (22) organisations who responded to this question agreed with the proposal. More than 65% of individual respondents agreed with the proposal, with patients providing the highest level of support (72%, 599).

Figure 5. To what extent do you agree or disagree that there should be an explicit duty on the HFEA and clinics to act to promote patient care and protection?2

The main theme from free text responses that referred to this proposal indicated that promotion of patient care and protection is important and should be included in legislative change, but clarity is needed on the term ‘patient’ and who this refers to.

There was consensus in the organisational and professional responses that promotion of patient care is important and should be a focus:

‘Overall, the general consensus is supportive of the proposed changes. The opportunity to contribute to these changes and modernisations are welcome with the overall act encompassing and focusing on patient care.’ [Royal College of Nursing]

Some organisations and professionals disagreed with the proposal as they perceived that the word ‘patient’ did not capture all relevant parties involved in fertility treatments:

‘I disagree with the wording of this statement as it omits reference to promoting the best interests of children who may be born as well as donor and surrogates (who are not patients). The duty of care should extend to all persons who are key stakeholders in the treatment process and its outcomes.’ [Professional – no affiliation provided]

Organisational and professional responses highlighted the importance of protecting the child born as a result of treatment, including those born from donor treatments:

‘ARCS [Association of Reproductive and Clinical Scientists] SAC [Scientific Advisory Committee] also felt it vital that the welfare of the child should remain a key component – arguably more so than patients. Currently the patients have a degree of protection through existing medical governance structures, although there is a recognition of the difference in fertility treatment. However, the wording in the question places no emphasis on welfare of the child – and this could be a powerful instrument to assist with introduction of new technologies/methods/techniques. If it is part of the Act to consider the welfare of the child then that would legislate for consideration of long-term health implications.’ [Association of Reproductive and Clinical Scientists]

‘Donor Conceived People should be included in the promotion of patient care and protection. The term ‘patient’ removes focus from the rights of DCP [donor conceived people], who may later approach the clinic for help. Clinics lose sight of the long-term implications for DCP and we must be considered underneath the umbrella or care and protection.’ [Donor Conceived Register]

Protection of the embryo was also noted as critically important and there was concern from the phrasing of this question that this may diminish at the expense of a focus on care and protection of the ‘patient’ as well as noting that broadening the Act beyond the embryo could be important:

‘The needs and desires of patients, as important as they are, should not come at the expense of the rights of human embryos, the views of wider society as legislated through Parliament, or the maintenance of public trust.’ [Right to Life UK]

‘The discrepancy between the intentions of the original Act (to protect gametes and embryos in vitro, and regulate research strictly) and the wider context in delivering of infertility service generally is noteworthy and outdated. Revision is essential but not easy in terms of the wider concern about the nature of protection for the embryo in minds of individuals and organisations.’ [Professional – Academic]

A minority of free text responses opposed this proposal, noting that this did not imply a lack of concern about patient care, but that they did not support the assertion that the Act is ‘silent on patient care’:

‘The statement that “the Act is silent on patient care” is not justified. The [HFE Act], as implemented, already includes patient care. Clinics are required to report adverse events, serious adverse events and serious adverse reactions.’ [British Fertility Society]

This minority felt that patient care and protection was already considered within the current inspection regime and that there was insufficient evidence to make such a significant change to the Act.

Treatment add-ons and marketing of fertility services were suggested areas to focus on within legislative changes regarding patient care and protection:

‘Patient-safety/care as a framework for the Act should be a priority to help ensure that patients are not, for example, pressured into agreeing to unnecessary and ineffective 'add-ons' to their fertility treatments.’ [Professional- Academic group or organisation]

‘Patient safety and promoting good practice

The proposals in this section of the consultation seem to us to offer a reasonable and proportionate response to the evolution of assisted conception services in the UK since the original framework legislation was enacted. However, as they represent a development in the rationale for regulation, rather than merely an updating of the regulatory tools, there is a case for this to be clearly articulated and subject to wide public consultation. In other words, it could be made more explicit that proposals aim to expand the Act’s remit to regulating the market, in order to protect the interests of patients who, by virtue of their situation, may be vulnerable to exploitation. In developing its function as a market regulator, with increased focus on the interests of patients, we hope the Authority also will continue to prioritise consideration of ethical and societal values around fertility treatments and embryology research.’ [Nuffield Council on Bioethics]

Responses from the patient and members of the public response groups that referred to this proposal also reflected a misinterpretation that the term ‘patient’ in the proposal did not clearly include all relevant parties.

Question 6 - Better regulatory tools to tackle poor patient care

There was support for the proposal for the HFEA to have a broader range of powers to tackle related fertility services not taking place in licensed clinics (Figure 6). Most (20) organisations that responded to this question agreed, and 13% (8) disagreed. Patients had the most support, with 65% (539) agreeing with the proposal. There was some disagreement from individuals responding as both a patient and professional with 17% (21) disagreeing with the proposal.

Figure 6. To what extent do you agree or disagree that the HFEA should have a broader range of powers to tackle related fertility services not taking place in licensed clinics?2

The main theme from free text responses that related to this proposal suggested that there is support for regulation of related fertility services that take place outside of fertility clinics, but more clarity was needed on what services would be included in this proposal.

Responses from organisations and professionals indicated that concerns about patient safety and fraud are some of the reasons underlying support for this proposal:

‘The HFEA should have greater powers to act in cases where fertility treatments take place outside of licensed clinics to protect patients from fraudulent and possibly dangerous services.’ [Professional – no affiliation provided]

However, responses showed that although this proposal was viewed as beneficial, further clarification was needed on what services this would include:

‘…extending the scope of the HFE Act to cover fertility treatments outside licenced clinics has potential to help clamp down on dangerous or fraudulent services but again more detail on the scope and methods is warranted before I could approve or reject this proposal. [Professional – Academic group or organisation]

A minority did not support widening the scope to regulate fertility related treatment as, for example, they perceived this as inconsistent with government direction to minimise regulatory burden. Other reasons for caution related to concern about limited resources meaning that attention may be drawn away from core regulatory responsibility:

‘Careful consideration should be given to limiting the scope of regulatory responsibility in these areas if powers here are to be extended to ensure that regulatory resources remain on core activities.’ [Professional – Academic group or organisation]

Some responses provided insight into which related fertility services should and should not be regulated, for example, online services. Suggestions were also given to reduce concerns about the provision of such services and increased education about the implications of unregulated ‘fertility services’ was recommended:

‘BICA are unsure how this proposal would work in practise, however we would support encouraging education around the implications of unregulated “fertility services”’ [British Infertility Counselling Association]

‘It is important to recognise the limits of the [HFEA] as a regulator, but we would welcome a wider conversation about private arrangements and whether there is scope for policy interventions and greater awareness raising that could help those who make private arrangements and the implications for the children of these arrangements.’ [Member of the public]

In addition, a minority of organisational and professional responses referred to broader consumer protection and suggested that working with other regulatory bodies would be useful:

‘ARCS [Association of Reproductive and Clinical Scientists] feel that it is important that the proposed changes do not result in pressure upon licenced centres, but strongly agree wider (though not necessarily greater) regulation is desirable – that could involve ceasing active promotion / advertising of things that do not have an evidence base or would not be legal in the UK situation (such as foreign clinics attending UK nationals at UK based shows / through web-based systems). We presume this will involve joint-working with CMA. This would need ability to be amended / updated. It also needs to understand what, if any relationships exist between licenced clinics and non-licensed services.’ [Association of Reproductive and Clinical Scientists]

Responses from the patient and members of the public response groups focused on the regulation of sperm donation outside of clinics which is beyond the scope of this consultation.

Question 7 – Making licensing decisions more efficient

There was overall support for the current appeals process to be changed (Figure 7). Most (19) organisations that responded to this question agreed with the proposal. The highest level of support was from professionals, with 56% (148) agreeing with the proposal. Individuals responding from the professional/patient response group disagreed to some extent (12%, 15 responses). Some (16%,129) patients expressed uncertainty when answering this question, which may be due to patients not being aware of current appeals processes.

Figure 7. To what extent do you agree or disagree that the current appeals process should be changed?2

There were a low number of free text responses that referred to this proposal and were primarily received from organisations. A key theme suggested was support to make the appeals process quicker and less resource intensive, so long as the effectiveness of the appeals process was maintained.

Although there was support for change to the appeals process, it was recommended that any changes, such as streamlining or speeding up the process, should not dimmish the effectiveness of the process for any parties involved, nor be diluted by attempts to reduce the cost:

‘On the one hand, it would appear sensible to make the process quicker and cheaper – for the HFEA and for clinics. The proviso, however, is that clinics must retain appropriate ability to defend themselves in this process, including maintaining an appropriate right of appeal.’ [The Evewell Group]

‘…we recognise the pressures related to inspection and the need to ensure that the appeals process is proportionate, balancing costs, maintaining quality services which adhere to regulations, avoiding unreasonable pressures on agencies and staff and upholding the wider public interest. As such the need for a rigorous approach to the appeals procedure is clear and should not be diluted by considerations of cost.’ [Project Group on Assisted Reproduction]

There was one response that indicated the current process is suitable:

‘This would give the HFEA too much power in these scenarios, where there are usually 2 points of view. In my opinion, these cases are very few and the current process though slow, allows for HFEA to [a]ffect its regulations, while clinics’ right to a fair appeal process is protected.’ [Professional – A professional or clinical group or organisation]

Question 8 – Making licensing decisions more efficient

There was support for the proposal for the HFEA to have more flexibility to make rules governing the setting of standard licence conditions, however some uncertainty was indicated in responses (Figure 8). Responses from organisations were mixed with around 20% (13) agreeing with the proposal, 15% (9) responding as unsure, and 8% (5) disagreeing. Around half of responses from individual respondent groups (609) agreed with the proposal.

Figure 8. To what extent do you agree or disagree that there should be more flexibility for the HFEA to make rules governing the setting of standard licence conditions?2

There were a low number of free text responses that referred to this proposal and these were primarily received from organisations. Of those responses, a key theme indicated that more clarity would be needed to understand this proposal.

Some free text responses endorsed the proposal for the HFEA to have more flexibility to set standard licence conditions to bring changes across the sector when needed:

‘The CMA strongly agrees that there should be more flexibility for the HFEA to make rules governing the setting of standard licence conditions. Where there are sector-wide issues there ought to be an effective mechanism by which the HFEA can bring about the desired changes across the sector as a whole.’ [Competition and Markets Authority]

Overall, responses from organisations referred to more clarity being needed on whether the proposal referred to legislation or implementation of standard conditions:

‘It is not clear whether the current process for changing standard conditions is a problem related to the legislation or its implementation. If it is a problem with the legislation, then this should be corrected by Parliament. If the problem is with its implementation, this could be improved without legislative change.’ [British Fertility Society]

Some respondents perceived that the suggested changes may mean that clinics would not be able to challenge new standard licence conditions. This was considered inconsistent with good regulatory conduct. An organised response from donor-conceived individuals and individual respondent free text responses suggested that standard licensing conditions should be informed by the long-term implications for donor-conceived individuals, however this was beyond the scope of the consultation.

Section 2: Access to donor information

In total, 1,202 responses were received for this section (Table 3). A significant number of those responding to the consultation from the patient response group had experience with donation services (see Individual respondent demographics section). This contrasts with the ‘average’ UK patient, where nearly 1 in 6 births using IVF in the UK are through donor conception.3 This section included three questions and 384 free text responses.

| Table 3. Total number of responses by response group for Section 2: Access to donor information. | ||

|---|---|---|

| Response group | Number of responses | Percentage |

| Organisation | 40 | 3% |

| Professional | 179 | 15% |

| Professional/patient | 95 | 8% |

| Patient | 611 | 51% |

| Members of the public | 277 | 23% |

| Total | 1,202 | 100% |

Question 1 – Donor anonymity

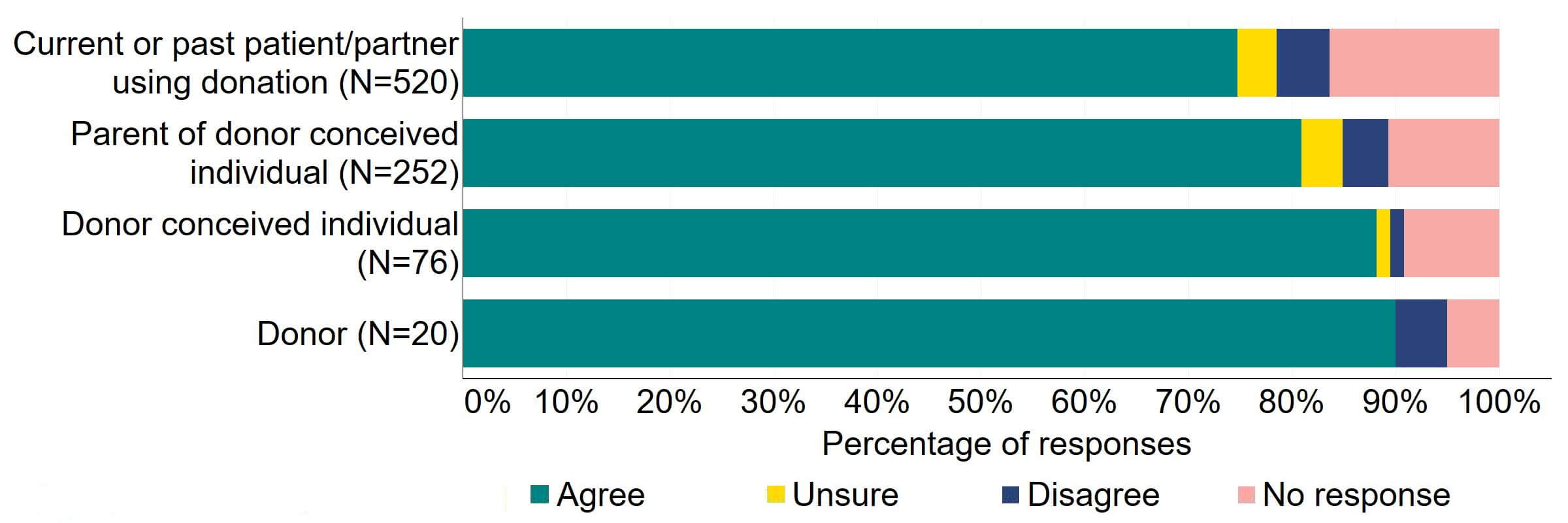

Overall, there was support across response groups for clinics to be required by law to inform donors and recipients of potential donor identification through DNA testing websites (Figure 9). Most (27) organisations that provided a response for this question supported the proposal. Over half of professionals, professional/patients, and patients agreed with the proposal.

Figure 9. To what extent do you agree or disagree that clinics should be required by law to inform donors and recipients of potential donor identification through DNA testing websites?2

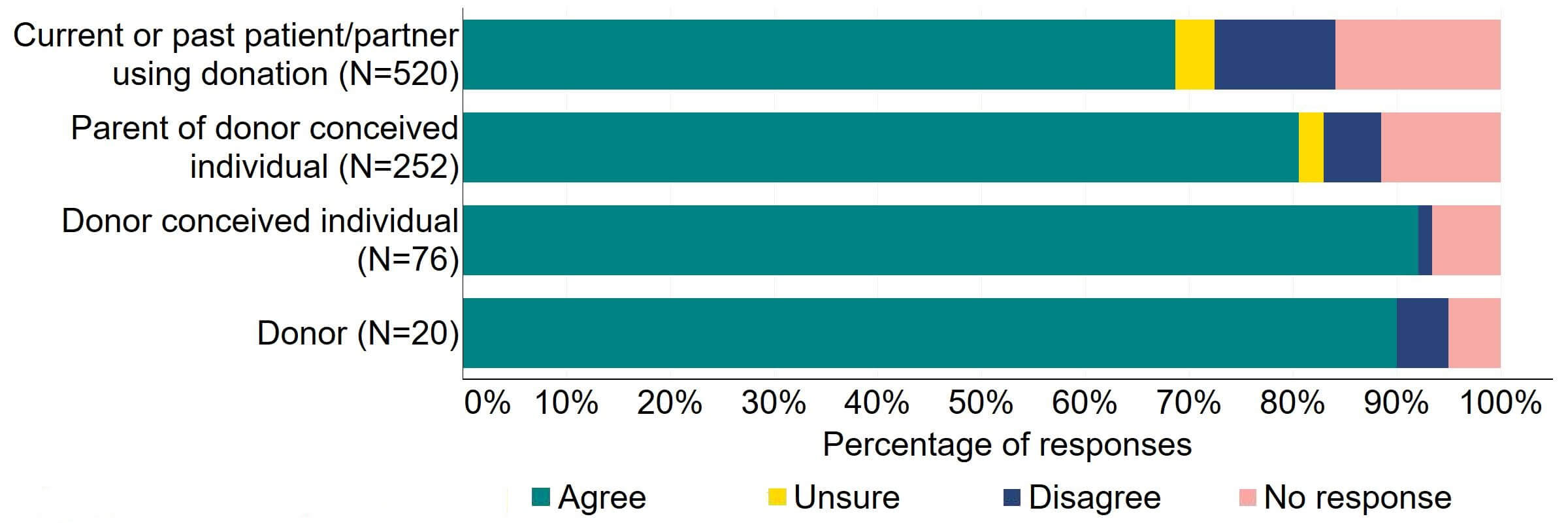

Figure 10 provides a more detailed breakdown of respondents who had experience relating to/with donor treatment. There was support for the proposal, with over three quarters agreeing across all groups. Responses from donors indicated the highest level of support (90%, 18 responses), although the numbers of responses from this group was small.

Figure 10. To what extent do you agree or disagree that clinics should be required by law to inform donors and recipients of potential donor identification through DNA testing websites?

Respondents broken down by patient type relating to donation

Overall, the key theme from free text responses that referred to this proposal indicated that there was support for clinics to be required to provide information to donors and recipients and legislative changes should not only be restricted to donor identification via DNA testing websites.

Organisational responses reflected support for sharing information with donors and recipients that donor identification may occur prior to the donor-conceived individual reaching 18 years old:

‘We welcome the recognition of the increasing possibilities for some parents and donor-conceived people to access, and make inferences based on, information through direct-to-consumer genetic testing and other online platforms. We agree that this should be reflected in the information and the counselling offered to donors and those seeking treatment with donor gametes. This is critical in ensuring that they can make their own choices and decisions on the basis of accurate and appropriate information.’ [Nuffield Council on Bioethics]

Some responses noted that DNA testing websites are only one route to donor identification and that this should be made clear in the information provided:

‘The background text indicates that there are several ways for connections to be made/discovered outside the HFEA route but the question only refers to DNA testing sites. We know that there are people using Facebook groups and clinic/donor information to discover connections as well as other means. It would be good to mention all possible routes, not just DNA testing.’ [Donor Conception Network]

Organisational responses highlighted the rapidly developing field of genetic testing and noted that this should be considered for any legislative change to ensure it is future proofed. Suggestions included providing detail of the specific technologies in the Code of Practice as opposed to primary legislation to facilitate flexibility:

‘Clinics should be subject to a legal obligation to inform donors and recipients about the possibility that, as a result of developing technologies, such as (but not limited to) DTCGT [direct to consumer genetic testing], any children born from donation could discover their donor’s identity before they are 18. Specific technologies, and related concerns, should be described in Guidance/CoP [Code of Practice], updated with sufficient regularity to ensure that clinics’ legal obligations to provide proper information can be supported.’ [The University of Manchester (The ConnecteDNA project)]

A minority disagreed or were unsure about making legislative changes. It was noted that guidance to share information is already provided in the Code of Practice4 and it was also highlighted that information should be shared as part of implications counselling:

‘This is covered by the Code of Practi[c]e as part of implications counselling; centres are inspected against the Code of Practi[c]e. If this is passed through legislation, does it imply all implications counselling information would require legislation?’ [Fertility Scotland National NHS Strategic Network]

Most responses from the patient response group were part of an organised response. This focused on the challenges of a person unexpectedly finding out they are donor-conceived, particularly as an adult, via DNA testing websites. These responses were beyond the scope of this consultation. Responses also referred to the alternative options that are being used to find information about donors and donor siblings, such as via social media.

Question 2 – Donor anonymity

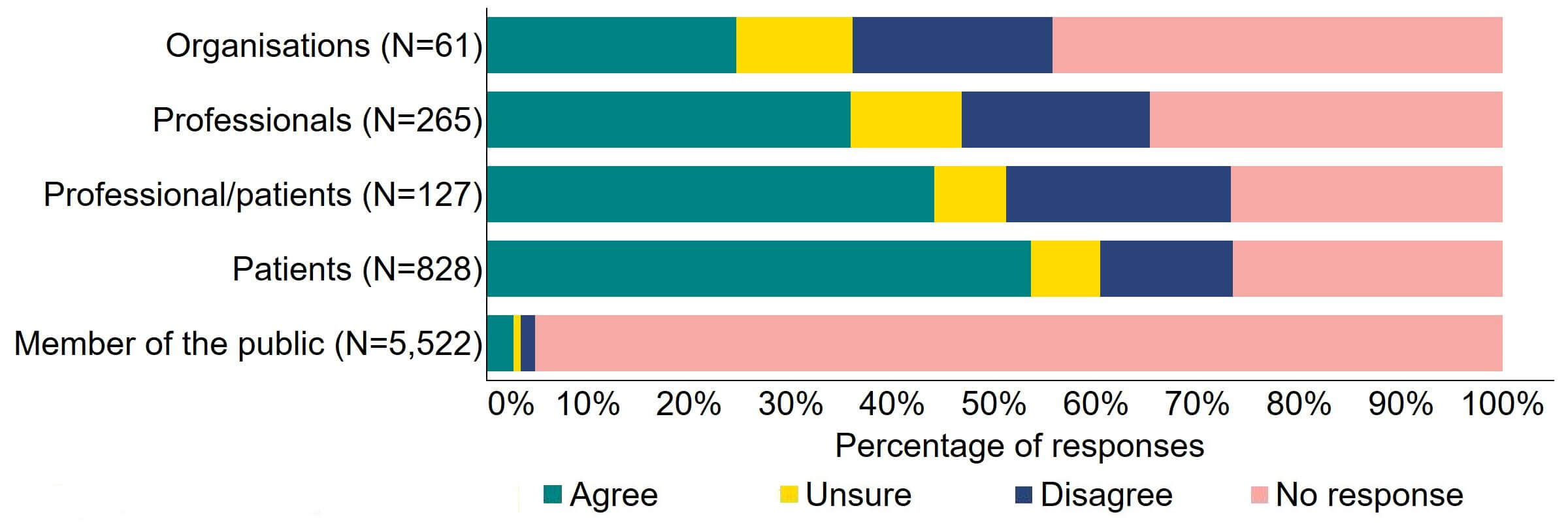

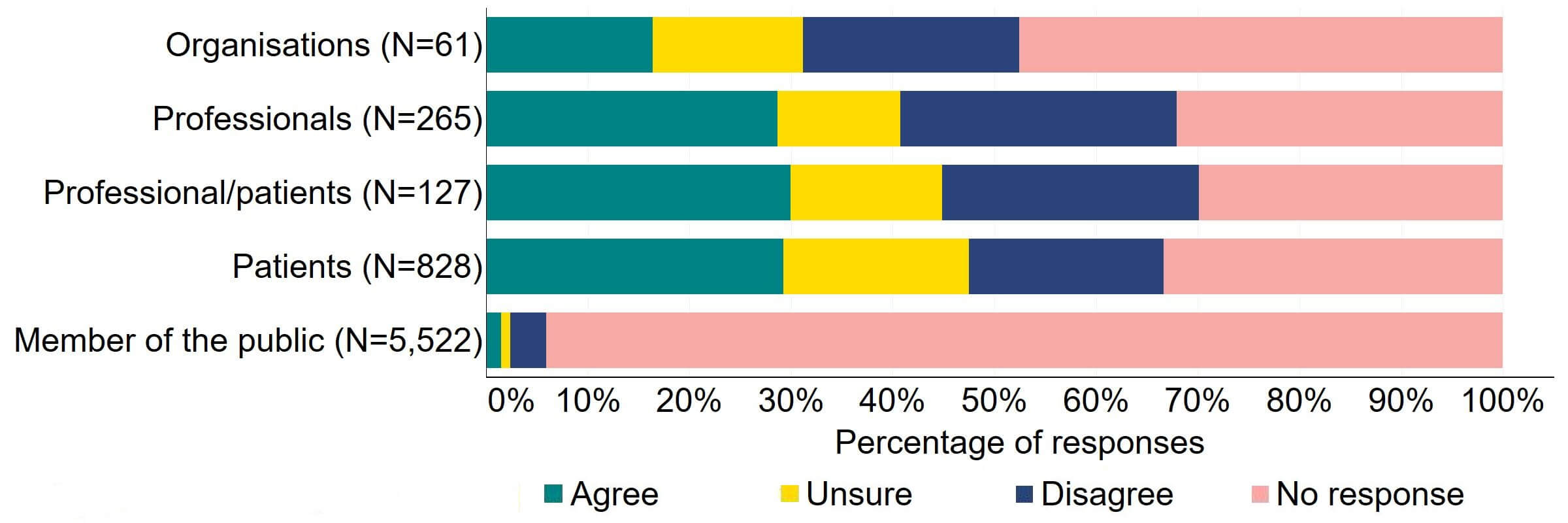

There were varied responses to the proposal to amend the Act to provide parental and donor choice to opt for anonymity until age 18 or identifiable information after the birth of a child (Figure 11). About a quarter (15) of responses from organisations agreed and 20% (12) disagreed. The highest level of agreement was from patients (444), and this can be explained to some extent by the further breakdown of respondents who had experience with donor treatment in Figure 12. Almost a half (44%) of patients/professionals agreed. Just over a third (36%) of professionals supported the proposal and just under 20% (49) disagreed.

Figure 11. To what extent do you agree or disagree that the Act should be amended to provide parental and donor choice to opt for anonymity until age 18 or identifiable information after the birth of a child?2

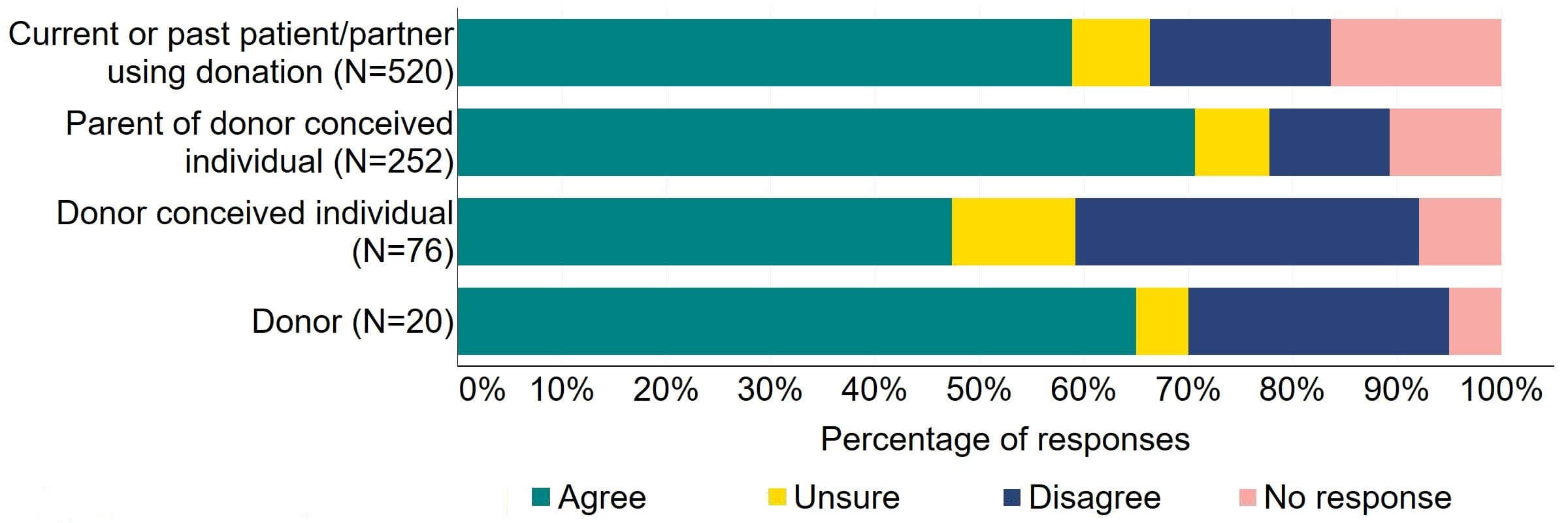

Figure 12 provides a more detailed breakdown of respondents who had experience with donor treatment. Most donors, parents of donor-conceived individuals, and patients/partner with current or past experience of donation agreed with the proposal (over 59%). Donor-conceived individuals gave a more varied response with just under half (47%, 36) agreeing and around a third (33%, 25) disagreeing.

Figure 12. To what extent do you agree or disagree that the Act should be amended to provide parental and donor choice to opt for anonymity until age 18 or identifiable information after the birth of a child?

Respondents broken down by patient type relating to donation

Overall, there were mixed free text responses to this proposal, and this was particularly apparent in organisational and professional free text responses. A key theme from these responses indicated that there was general support for earlier information access for donor-conceived individuals, but a dual track system was not fully supported.

Organisations and professionals supported changes to legislation to enable earlier access to donor information but there were varied responses on whether this should be at birth, aged 16, or other ages. A dual track system was not supported overall and those who did support this proposal raised some concerns. Reasons for lack of support included, but were not limited to, creating inequality between those who can and cannot access information and challenges to administrate this type of system:

‘We agree with the general move towards more flexibility and opportunities for earlier connections where mutually agreed. However, we would like to flag that there are a number of important and complex issues that this consultation doesn’t address and which would be worthy of discussion and debate. This new arrangement changes the relationship from one between HFEA and DCP to one between HFEA and parents. Similarly, donors will be connected with parents rather than with the DCP at 18. Currently, it is the future child (once they turn 18) that the HFEA has a responsibility to with regard to sharing information. All donors at present must fit the same criteria regarding contact, which means prospective parents having treatment in a UK clinic do not have to make a choice on this and are all, broadly speaking, in the same situation. Under the proposed new system, the HFEA has a relationship with the parents not the DCP and it will be their responsibility to decide what kind of donor to use and whether, when and how to get contact information and share with their children. This shift is worth acknowledging.’ [Donor Conception Network]

Respondents also felt that donor-conceived individuals should continue to make the choices about information access:

‘Parental and donor preferences must not override/limit the rights of the donor conceived person. Again, we strongly encourage nothing but transparency from birth.’ [Donor Conceived Register]

‘…I disagree with the idea that parents/guardians should be able to access identifiable information after the birth of the child. This places the information with the parents, and not with the donor-conceived person. This is unjustified, as donor information pertains to the donor-conceived person, not the parents. It is potentially formative for the donor-conceived person’s identity, not that of the parents. Therefore, it should be the donor-conceived person who makes decisions about access to this information. Protecting the autonomy of donor-conceived individuals requires them to decide the level of importance they attach to information about their donor(s) and whether/when they wish to access it.’ [Professional – Academic group or organisation]

Although there was overall support for donor information disclosure before the age of 18, some concerns were raised about whether this would result in a decrease in new donors:

‘I imagine that the prospect of being contacted earlier will make donors think more about whether they want to donate or not. Given the number of UK donors available I would imagine the numbers will decrease.’ [Professional – A professional or clinical group or organisation]

‘Ultimately I think there should be choice available to both donors and recipients on when they find out but I wouldn’t want to take away any choice that would then put off donors and limit the already low supply. [Patient]

Responses from organisations and professionals reflected other concerns about early information disclosure. Concerns included, but were not limited to, questions raised about child safeguarding, challenges of navigating relationships between donors and donor-conceived individuals, and whether those involved would have the option to change their mind over time. Some responses across all groups also queried whether any future legislative changes may be applied retrospectively, including an organised response calling for retrospective lifting of donor anonymity from those who donated between 1990-2005. This organised response also suggested birth certificate reform (i.e. include details that a person is donor-conceived) for all donor-conceived individuals.

Another key theme was the importance of donor sibling relationships and responses included suggestions to make the Donor Sibling Link accessible for donor-conceived individuals under the age of 18.

Responses highlighted the importance of donor sibling relationships to donor-conceived individuals and their parents. Some responses noted that seeking information about donor siblings often underpins the decisions to use DNA testing websites and other methods to obtain donor information. Suggestions for legislative and non-legislative changes were provided, to allow donor-conceived individuals under the age of 18 to access the Donor Sibling Link should be considered:

‘We are not sure why the consultation is only asking about potential connection with the donor, where the introductory text also mentions half siblings. For many families, particularly solo mum families, the interest is as much, possibly more, in being able to connect with their child’s half siblings through the donor from an early age.’ [Donor Conception Network]

‘Whilst the HFEA is making recommendations to the government for proposed changes to the legislation to ensure it remains relevant, we’d like to propose the HFEA also submit a recommendation for families to be able to connect with donor siblings through official channels (via the UK Donor Sibling Link) before the donor conceived person turns 18.’ [Donor Sibling Connections UK]

It was also suggested that people who had parents who were donors, but were not donor-conceived themselves, should also have access to the Donor Sibling Link:

‘It’s a shame that there is no mention of the donor’s own children as they are just as closely connected to any children created and therefore are also interested parties and may be keen to have information and/or contact.’ [Donor Conception Network]

A further theme from responses, primarily from individuals that formed an organised response as well as some organisational responses, related to the importance of accurate contact details and up-to-date medical records for donors. Some of these responses suggested that financial penalties should be applied if medical records are not provided to donor-conceived individuals:

‘We are also concerned that the state holds data that is fundamental to the health of donor adults but does not forward that information to the NHS and to donor conceived adults’ healthcare workers. This means that the state is not properly informing GPs and other medical practitioners of the health circumstances of donor conceived adults and thus hindering their ability to effectively advise on health issues.’ [Patient]

Question 3 – Mandatory implications counselling

There was support for the proposal for the Act to require all donors and recipients to have implications counselling before starting treatment (Figure 13). Most (31) organisations who answered this question also supported it. Over two thirds of individuals, including professionals, professional/patients, and patients, agreed with this proposal. Across all groups, less than 6% disagreed with the proposal.

Figure 13. To what extent do you agree or disagree that the Act should require all donors and recipients to have implications counselling before starting treatment?2

Figure 14 provides a more detailed breakdown of respondents who had experience with donor treatment. There was support for the proposal, with over 65% agreeing across all groups. Responses from donor-conceived individuals indicated the highest level of support (70, 92%), closely followed by donors with 90% (18) agreeing with the proposal.

Figure 14. To what extent do you agree or disagree that the Act should require all donors and recipients to have implications counselling before starting treatment?

Respondents broken down by patient type relating to donation

Overall, responses that referred to this proposal reflected clear support for mandatory implications counselling for donors and recipients prior to starting treatment, noting that this needs to be high quality.

Organisational and professional responses indicated support for this proposal and provided reasons that include the donor and recipients having the opportunity to fully discuss the implications:

‘BICA strongly agree that all donors and all recipients together with their partners must have implications counselling prior to treatment.’ [British Infertility Counselling Association]

Organisational and professional responses also provided further information about what would contribute to the usefulness of mandatory implications counselling. This included, but was not limited to, the counselling being offered by qualified counsellors and including multiple sessions. It was highlighted that sessions should focus on the welfare of the donor-conceived individual and the long-term implications of being a parent of a donor-conceived individual:

‘The Act should also require that such counselling be offered by qualified counsellors (ideally accredited by the British Infertility Counselling Association).’ [University of Manchester, ConnecteDNA Project]

‘Implications discussions facilitated by a specialist, experienced fertility counsellor attuned to individuals’ emotional perspective, couple dynamics and can contextualise the material in a sensitized, non-judgemental yet congruent manner offers the necessary conditions to properly inform consent about the life-long aspects of becoming a parent to a donor conceived child, considering the needs of a donor conceived person and being the donor.’ [Professional– A professional or clinical group or organisation]

Many organisational and professional responses highlighted the importance of distinguishing implications counselling from therapeutic counselling. Some suggested alternative language for implications counselling, including ‘implications sessions’:

‘BICA are aware of the confusion of the terminology between “therapeutic” (voluntary) and “implications” counselling and advocate for the latter being mandated with potential consideration to the terminology of such sessions (implications sessions?) being amended to provide a clear distinction.’ [British Infertility Counselling Association]

Many responses from the patient and members of the public response groups indicated support for mandatory implications counselling. Organised responses across the organisation and patient response groups also referred to a need to strengthen the inspection of implications counselling. It was particularly emphasised that this provision needs to be high quality, focus on the welfare of the donor-conceived individual, and be offered independently from the clinic:

‘Counselling must be mandatory for both Donors and Recipients. Counselling must be robust and must focus on the welfare of the Donor Conceived Person being created. There is a conflict of interest if the counselling is conducted by the clinic.’ [Donor Conceived Register]

A minority of responses from the patient response group did not support mandatory implications counselling, with some considering that this was unnecessary for patients in same-sex couples. Some indicated that their experience of implications counselling felt similar to a ‘tick box’ exercise:

‘Same-sex female couples are very well aware of why they are using donor sperm and any implications. The counselling for this does not feel relevant.’ [Patient]

Section 3: Consent

In total, 5,860 responses were received for this section (Table 4) which included three questions and 868 free text responses.

| Table 4. Total number of responses by response group for Section 3: Consent. | ||

|---|---|---|

| Response group | Number of responses | Percentage |

| Organisation | 42 | 1% |

| Professional | 185 | 3% |

| Professional/patient | 90 | 2% |

| Patient | 563 | 10% |

| Members of the public | 4,980 | 85% |

| Total | 5,860 | 100% |

Question 1 - Consent to treatment and legal parenthood

There was a varied response to the proposal to simplify the current consent regime in ways that continue to provide protection to patients (Figure 15). From the organisations that responded to this question, 13 disagreed with the proposal and 10 agreed. Just under one third (29%) of professionals (76), professional/patients (38), and patients (242) supported this proposal. Around a quarter of professionals (72) and professional/patients (32) disagreed with the proposal.

Figure 15. To what extent do you agree or disagree that the current consent regime could be simplified (for example to an ‘opt out’ model) in ways that continue to provide protection to patients?2

The overarching theme from free text responses that referred to this proposal indicated that overall, there is support for simplifying the current consent regime, but an ‘opt out’ model is not the preferred option for this.

There was agreement from organisational and professional responses that the current consent regime needs simplifying:

‘There is strong agreement that the consent process needs to be simplified. This must be a major focus of any revision of the Act.’ [British Fertility Society]

A small number of respondents supported the ‘opt out’ model, noting that this option would facilitate patient choice on how they provide consent:

‘(STRONGLY AGREE) This will reduce duplication and simplify information for patients. The “opt out” model was likened to Computer Cookies which included options of either agreeing to everything or reviewing each piece of information individually. The usefulness of consent forms in the Court of Law was considered, however, providing coherent information was deemed more appropriate than numerous consent forms. Consent forms often do not stand up to scrutiny in the Court of Law. Consent forms are becoming more complex as additional information is added to them. What would a change of legislation consist of, and can simplifying consent forms start now?’ [Fertility Scotland National NHS Strategic Network]

‘This is fine as long as patients are fully informed and it is clear they have the option to opt in/opt out.’ [Patient]

However, overall, concerns were highlighted about the implementation of an ‘opt out’ model. Some organisational responses suggested that lack of support for the proposal was due to unease in how the ‘opt out’ model would relate to informed consent:

‘Opt-out model of consent [-] We strongly disagree with the legal concept of opt-out consent in relation to healthcare. We are concerned that this would undermine the taking of Montgomery-compliant informed consent and leave patients who are unsure about the technicalities of some of the options giving consent to aspects that in an opt-in model they would have sought further information about.’ [British Pregnancy Advisory Service]

Other free text responses raised concerns an ‘opt out’ model could lead to more complexities that need to be resolved in court:

‘Actively ‘opting-in’ and consenting to each element of treatment or scenario is vital to avoid future misunderstandings and problems that would have to be resolved by the courts. Many unexpected things can go wrong in fertility treatment. Thus, instead of making the situation easier and simpler, the opt-out system may in fact make it more complex and difficult.’ [Scottish Council on Human Bioethics].

‘It would also not avoid court litigation, if this is what the HFE Authority is intending to do, as more flexibility simply means more questions about boundaries, and these tend to end up in court for clarification.’ [Professional/patient]

It was also noted that the ‘opt out’ model may not be suitable for fertility treatment specifically. Reasons included lack of responsiveness to the complexities around consent for fertility treatment and not considered a patient-focused model:

‘Opt out is not suitable for something as complex and impactful as fertility treatment and would put some couples who may already be in a difficult position of having to ‘withdraw consent’ from each other, which is needlessly negative.’ [Patient]

‘The language of ‘taking consent’ used in the consultation seems out of step with patient-focused healthcare in which consent is thought of as sought and given, and the giving of consent is increasingly understood as a dynamic and relational process, rather than a one-off event.’ [Professional – Academic group or organisation]

Responses from the patient and members of the public response groups indicated support in the consent process needing simplification. Consistent with professional responses, it was noted that they found current consent forms to be lengthy and difficult to complete:

‘The consent process has been such a challenging part of the [IVF] process. It’s hard to understand, complex and doesn’t encourage people to actually read what they are signing.’ [Patient]

Some concerns were raised that the ‘opt out’ model may adversely affect particular groups. The patient response group also referred to the complexities of posthumous consent for use of gametes and embryos. Some called for modernisation and simplification of this area of consent.

Question 2 - Consent to disclosure

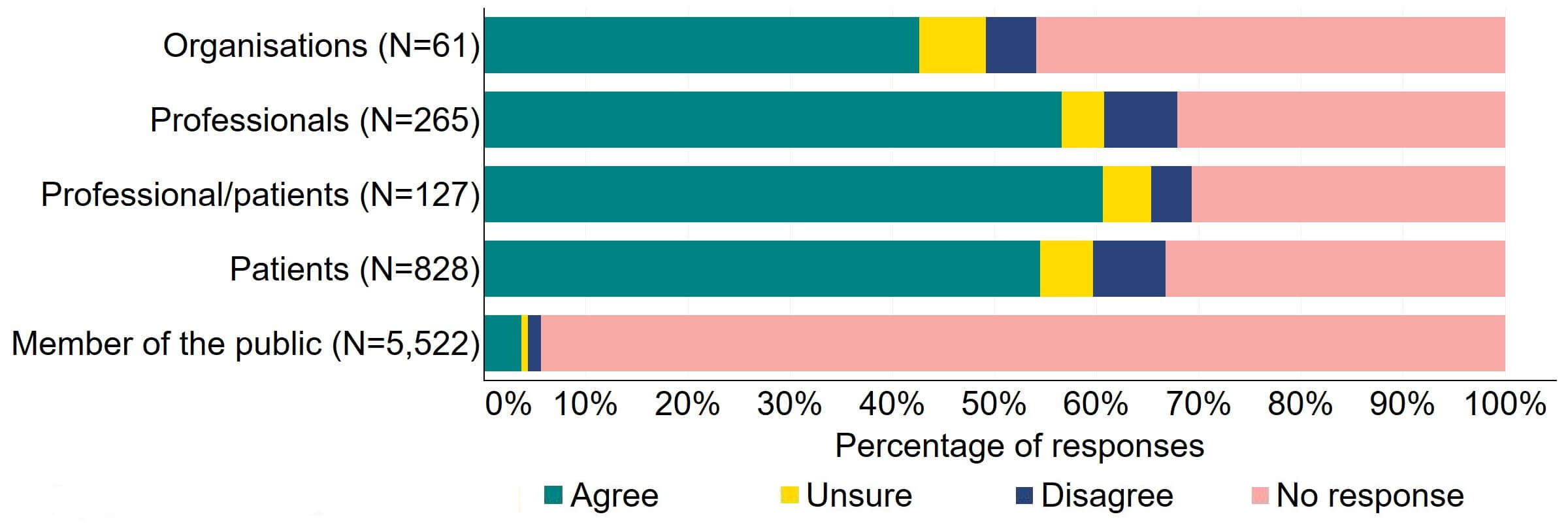

There was overall support for sharing of fertility patient data in non-fertility medical settings in line with current practice for sharing of other patient/medical data between healthcare providers (Figure 16). Most (26) organisations that answered this question agreed with the proposal. More than half of professionals (150) and patients (451) agreed with this proposal. Professional/patients had the highest level of support for the proposal at 61% (77).

Figure 16. To what extent do you agree or disagree that the sharing of fertility patient data in a non-fertility medical setting should be brought in line with the current regulations for the sharing of other patient/medical data between healthcare providers?2

The overall theme from free text responses that referred to this proposal indicated that there was support for sharing of fertility data across medical settings, with some individual responses suggesting an option not to share data should remain.

Organisations and professionals supported changes to legislation to bring the sharing of fertility patient data between healthcare providers in line with other areas of health:

‘Legislation should be amended such that the sharing of medical data about fertility treatment is consistent with general healthcare provision in the UK.’ [British Fertility Society]

Some noted that the current restrictive legislation was perceived as outdated and no longer justified:

‘…the special status of medical secrecy that applies to assisted conception has long since ceased to be justifiable.’ [Progress Educational Trust]

One of the reasons across all response groups that underpinned the support for this proposal appeared to refer to issues of patient safety when information is not shared:

‘Patient safety is endangered by the fact that [patients] fertility medical records are not able to be accessed by other medical professionals outside of the fertility service (e.g. a fertility patient attends in an emergency out-of-hours due to complications from fertility treatment but the treating team have no access to information regarding what treatment they have received).’ [Professional – A professional or clinical group or organisation]

Sharing fertility information with other healthcare providers was considered an important part of patient care, particularly with obstetrics and gynaecology services. Some responses also referred to data sharing playing an important role in protecting the welfare of the child.

Some individuals who responded from the professional and patient response groups suggested there should still be options for patients to choose not to share their data. This was perceived as consistent with data protection principles and particularly relevant for patients who have treatment with donor eggs, sperm, or embryos:

‘Re sharing people's fertility records with general NHS records, many patients still welcome the privacy afforded by the Act, especially in relation to the use of donated gametes. I would suggest a middle road be adopted where patients are given the choice.’ [Professional – A professional or clinical group or organisation]

‘I think it is patient choice how much the NHS is informed about their fertility treatment and what information (such as donor) is disclosed.’ [Patient]

Question 3 – Consent to research

Across most response groups, there was support for the proposal that consent for donating embryos should be extended to allow patients, who wish to, to give consent to research embryo banking (Figure 17). Around two thirds (39) of organisations responded to this question, with around a third (22) agreeing and just under a quarter (13) disagreeing. Over a half of professionals (146), professional/patients (64), and patients (448) agreed with the proposal. Around 90% of members of the public answered this question and most (86%) disagreed with the proposal.

Figure 17. To what extent do you agree or disagree that consent for donating embryos should be extended to allow patients who wish to, to give consent to research embryo banking?2

There were several themes in the responses to this proposal. Some organisational responses and most responses from members of the public reflected a broad opposition to the use of human embryos in research. This is outside the remit of this consultation and are therefore not discussed in this section.

Overall, there was some support for generic consent to research embryo banking due to the challenges of the current consent to research regime.

Organisational responses noted the current processes to donate embryos to research are reliant on clinics being linked with research projects or sustaining relationships with research groups:

‘Currently consent relies on relationships between researchers and fertility clinics. Where these relationships are not in place, patients don’t have the opportunity to donate their embryos for research and their embryos are discarded when no longer needed for treatment.’ [Medical Research Council & Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council, on behalf of UK Research and Innovation]

It was also noted that some aspects of the process of embryo donation to research are considered impractical, including the movement of embryos from the treatment centre to the research centre. Due to practical barriers, it was highlighted that, in some instances, when patients wish to donate embryos to research, they are not able to do so:

‘One major challenge continues to be the lack of access by research laboratories to pre-implantation human embryos. Fertility patients who want to donate their embryos to research face many challenges, for example, if their clinics do not have links with research projects or these projects are not active at the time the donation is due to take place.’ [The Wellcome Trust]

‘The current system fails patients and fails embryo research. Many practical impediments currently militate against the donation of embryos for research, making donation difficult even in instances where the patient is eager to donate and the relevant clinic is keen to support research.’ [Progress Educational Trust]

Organisational and professional responses also noted the challenges in being able to contact donors meaning that embryos may be discarded before being used in research. Some responses indicated that generic consent to a research embryo bank could overcome some of these challenges and facilitate more embryo research to be carried out:

‘Embryos are such a precious and rare resource that giving more general consent would allow for more valuable research to be carried out than at present.’ [Professional – A professional or clinical group or organisation]

The organisational and professional responses emphasised that a key factor underpinning a successful model for consent to donate embryos to research is that patients are able to make informed decisions and that they should be supported to make this decision:

‘It is therefore important that it is clearly explained to individuals what the purpose and potential benefits of embryo research is to improve transparency and build trust between the public and researchers which in turn will improve the availability of embryos for research.’ [Genetic Alliance UK]

Some opposition to generic consent for a research embryo bank was provided in the responses citing reasons such as concern about commercialisation.

Although there was support for research embryo banking, some organisational responses focused on the practicalities that would need to be considered when setting up and maintaining an embryo bank, with examples including infrastructure requirements and appropriate governance:

‘It is important to highlight that any national embryo banking initiative would need careful consideration, in terms of availability of funding, value for money and appropriate governance for procuring, storage and release of embryos.’ [Medical Research Council & Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council, on behalf of UK Research and Innovation]

Across all response groups, particularly from organisations, there was support for patients to retain the option to consent to specific research projects or types of research, e.g., publicly funded versus pharmaceutical research:

‘Agree in principle with a research embryo bank but the patients/donors should be allowed to opt out of some types of research uses e.g. pharmaceutical testing.’ [Semovo]

Section 4: Scientific developments

In total, 5,590 responses were received for this section (Table 5) which included two questions and 785 free text responses.

| Table 5. Total number of responses by response group for Section 4: Scientific developments. | ||

|---|---|---|

| Response group | Number of responses | Percentage |

| Organisation | 43 | 1% |

| Professional | 173 | 3% |

| Professional/patient | 90 | 2% |

| Patient | 494 | 9% |

| Members of the public | 4,790 | 86% |

| Total | 5,590 | 100% |

Question 1 – How regulation can best support innovation

Across most response groups, there was support for the Act to explicitly give the HFEA greater discretion to support innovation in treatment (Figure 18). Just under half (15) of organisations that responded to this question agreed with the proposal and 13 disagreed. Over 40% of professionals (128), professional/patients (53) and patients (361) agreed with the proposal. Almost 90% of members of the public responded to this question, with most (84%) disagreeing with the proposal.

Figure 18. To what extent do you agree or disagree that the Act should explicitly give the HFEA greater discretion to support innovation in treatment?2

Many free text responses to this section referred interchangeably to the proposals relating to consent to research (Section 3, question 3) and innovation. Most of the free text responses from members of the public and some organisations reflected a broader opposition to the use of human embryos in research which is outside the remit of this consultation and are therefore not discussed in this section.

Overall, a key theme indicated that there was some support for greater discretion to support innovation, for example via sandboxes, to improve the take up of potentially useful scientific developments.

Organisational responses indicate that this support was driven by acknowledgment that greater discretion would be associated with improving the timeliness of access to scientific development: